Copy of the article Linear Sequential Unmasking–Expanded (LSU-E): A general approach for improving decision making as well as minimizing noise and biais, Forensic Science International: Synergy, Volume 3, 2021, 100161, with author agreement (contact : [email protected])

All decision making, and particularly expert decision making, re quires the examination, evaluation, and integration of information. Research has demonstrated that the order in which information is pre sented plays a critical role in decision making processes and outcomes. Different decisions can be reached when the same information is pre sented in a different order [1,2]. Because information must always be considered in some order, optimizing this sequence is important for optimizing decisions. Since adopting one sequence or another is inevitable —some sequence must be used— and since the sequence has important cognitive implications, it follows that considering how to best sequence information is paramount.

In the forensic sciences, existing approaches to optimize the order of information processing (sequential unmasking [3] and Linear Sequential Unmasking [4]) are limited in terms of their narrow applicability to only certain types of decisions, and they focus only on minimizing bias rather than optimizing forensic decision making in general. Here, we introduce Linear Sequential Unmasking–Expanded (LSU-E), an approach that is applicable to all forensic decisions rather than being limited to a particular type of decision, and it also reduces noise and improves forensic decision making in general rather than solely by minimizing bias.

Cognitive background

All decision making is dependent on the human brain and cognitive processes. Of particular importance is the sequence in which information is encountered. For example, it is well documented that people tend to remember the initial information in a sequence better —and be more strongly impacted by it— compared to subsequent information in the sequence (see the primacy effect [5,6]). For example, if asked to memorize a list of words, people are more likely to remember words from the beginning of the list compared to the middle of the list (see also the recency effect [7]).

Critically important, the initial information in a sequence is not only remembered well, but it also influences the processing of subsequent information in a number of ways (see a simple illustration in Fig. 1). The initial information can create powerful first impressions that are difficult to override [8], it generates hypotheses that determine which further information will be heeded or ignored (e.g., selective attention [[9], [10], [11], [12]]), and it can prompt a host of other decisional phenomena, such as confirmation bias, escalation of commitment, decision momentum, tunnel vision, belief perseverance, mind set and anchoring effects [[13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19]]. These phenomena are not limited to forensic decisions, but also apply to medical experts, police investigators, financial analysts, military intelligence, and indeed anyone who engages in decision making.

Fig. 1. A simple illustration of the order effect: Reading from left to right, the first/leftmost stimulus can affect the interpretation of the middle stimulus, such that it reads as A-B-14; but reading the same stimuli, from right to left, starting with 14 as the first stimulus, often makes people see the stimuli as A-13-14, i.e., the middle stimulus as a ‘13’ (or a ‘B’) depending on what you start with first.

As a testament to the power of the sequencing of information, studies have repeatedly found that presenting the same information in a different sequence elicits different conclusions from decision-makers. Such effects have been shown in a whole range of domains, from food tasting [20] and jury decision-making [21,22], to countering conspiracy arguments (such as anti-vaccine conspiracy theories [23]), all demonstrating that the ordering of information is critical. Furthermore, such order effects have been specifically shown in forensic science; for example, Klales and Lesciotto [24] as well as Davidson, Rando, and Nakhaeizadeh [25] demonstrated that the order in which skeletal material is analyzed (e.g., skull versus hip) can bias sex estimates.

Bias background

Decisions are vulnerable to bias — systematic deviations in judgment [26]. This type of bias should not be confused with intentional discriminatory bias. Bias, as it is used here, refers to cognitive biases that impact all of us, typically without intention or even conscious awareness [26,27].

Although many experts incorrectly believe that they are immune from cognitive bias [28], in some ways experts are even more susceptible to bias than non-experts [[27], [29], [30]]. Indeed, the impact of cognitive bias on decision making has been documented in many domains of expertise, from criminal investigators and judges, to insurance underwriters, psychological assessments, safety inspectors and medical doctors [26,[31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36]], as well as specifically in forensic science [30].

No forensic domain, or any domain for that matter, is immune from bias.

Bias in forensic science

The existence and influence of cognitive bias in the forensic sciences is now widely recognized (‘the forensic confirmation bias’ [27,37,38]). In the United States, for example, the National Academy of Sciences [39], the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology [40], and the National Commission on Forensic Science [41] have all recognized cognitive bias as a real and important issue in forensic de cision making. Similar findings have been reached in other countries all around the world—for example, in the United Kingdom, the Forensic Science Regulator has issued guidance about avoiding bias in forensic work [42], and in Australia as well [43].

Furthermore, the effects of bias have been observed and replicated across many forensic disciplines (e.g., fingerprinting, forensic pathol ogy, DNA, firearms, digital forensic, handwriting, forensic psychology, forensic anthropology, and CSI, among others; see Ref. [44] for a review)—including among practicing forensic science experts specif ically [30,45–47]. Simply put, no forensic domain, or any domain for that matter, is immune from bias.

Minimizing bias in forensic science

Although the need to combat bias in forensic science is now widely recognized, actually combating bias in practice is a different matter. Within the pragmatics, realities and constraints of crime scenes and forensic laboratories, minimizing bias is not always a straightforward issue [48]. Given that mere awareness and willpower are insufficient to combat bias [27], we must develop effective —but also practical— countermeasures.

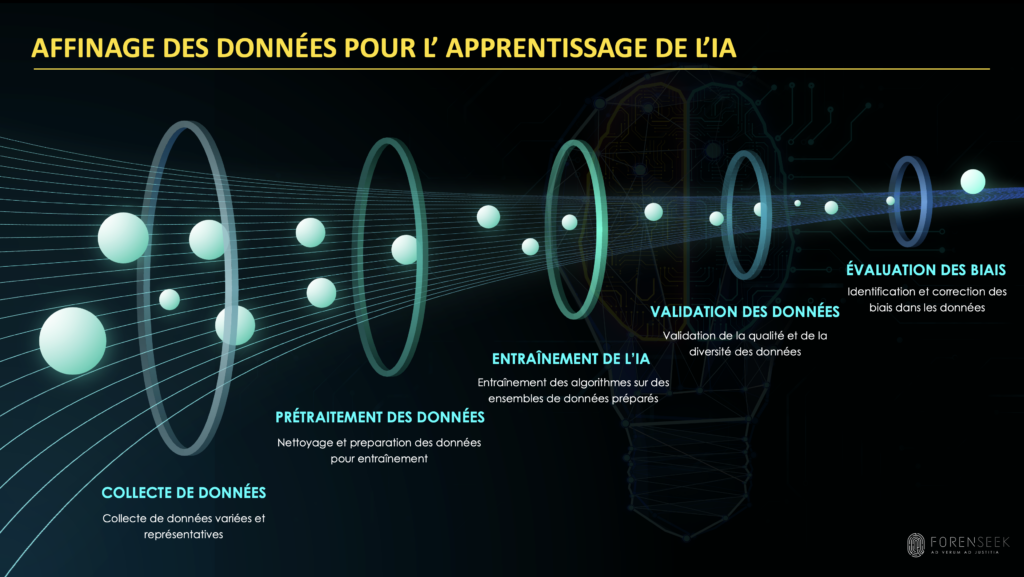

Linear Sequential Unmasking (LSU [4]) minimizes bias by regulating the flow and order of information such that forensic decisions are based on the evidence and task-relevant information. To accomplish this, LSU requires that forensic comparative decisions must begin with the ex amination and documentation of the actual evidence from the crime scene (the questioned or unknown material) on its own before being exposed to the ‘target’/suspect (known) reference material. The goal is to minimize the potential biasing effect of the reference/’target’ on the evidence from the crime scene (see Level 2 in Fig. 2). LSU thus ensures that the evidence from the crime scene -not the ‘target’/suspect- drives the forensic decision.

This is especially important since the nature of the evidence from the crime scene makes it more susceptible to bias, because –in contrast to the reference materials- it often has low quality and quantity of information, which makes it more ambiguous and malleable. By examining the crime scene evidence first, LSU minimizes the risk of circular reasoning in the comparative decision making process by pre venting one from working backward from the ‘target’/suspect to the evidence.

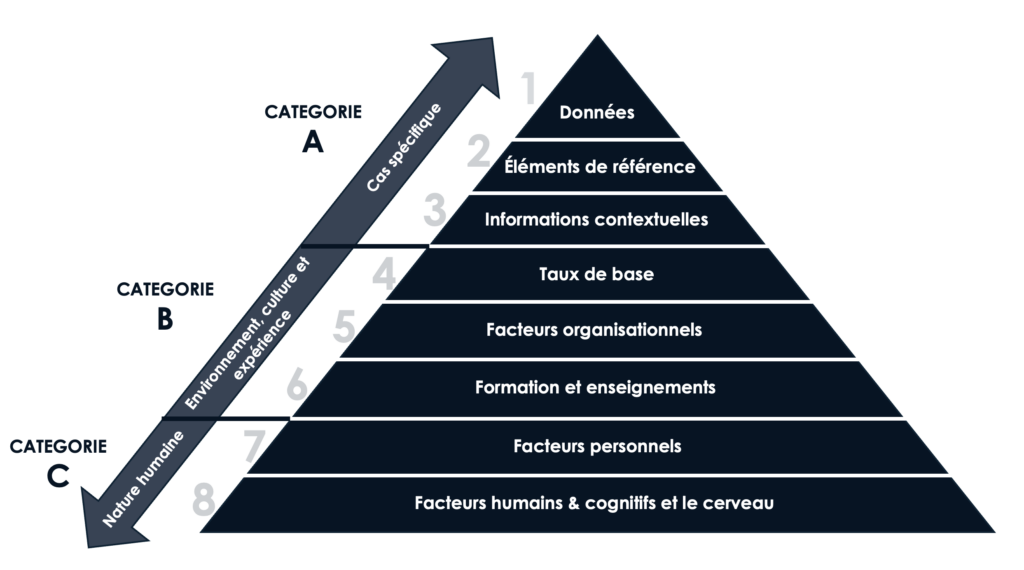

Fig. 2. Sources of cognitive bias in sampling, observations, testing strategies, analysis, and/or conclusions, that impact even experts. These sources of bias are organized in a taxonomy of three categories: case-specific sources (Category A), individual-specific sources (Category B), and sources that relate to human nature (Category C).

LSU limitations

By its very nature, LSU is limited to comparative decisions where evidence from the crime scene (such as fingerprints or handwriting) is compared to a ‘target’/suspect. This approach was first developed to minimize bias specifically in forensic DNA interpretation (sequential unmasking [3]). Dror et al. [4] then expanded this approach to other comparative forensic domains (fingerprints, firearms, handwriting, etc.) and introduced a balanced approach for allowing revisions of the initial judgments, but within restrictions.

LSU is therefore limited in two ways: First, it applies only to the limited set of comparative decisions (such as comparing DNA profiles or fingerprints). Second, its function is limited to minimizing bias, not reducing noise or improving decision making more broadly.

In this article, we introduce Linear Sequential Unmasking—Expanded (LSU-E). LSU-E provides an approach that can be applied to all forensic decisions, not only comparative decisions. Furthermore, LSU-E goes beyond bias, it reduces noise and improves decisions more generally by cognitively optimizing the sequence of information in a way that maximizes information utility and thereby produces better and more reliable decisions

Linear Sequential Unmasking—Expanded (LSU-E)

Beyond comparative forensic domains

LSU in its current form is only applicable to forensic domains that compare evidence against specific reference materials (such as a suspect’s known DNA profile or fingerprints—see Level 2 in Fig. 2). As noted above, the problem is that these reference materials can bias the perception and interpretation of the evidence, such that interpretations of the same data/evidence vary depending on the presence and nature of the reference material —and LSU aims to minimize this problem by requiring linear rather than circular reasoning.

However, many forensic judgments are not based on comparing two stimuli. For instance, digital forensics, forensic pathology, and CSI all require decisions that are not based on comparing evidence against a known suspect. Although such domains may not entail a comparison to a ‘target’ stimulus or suspect, they nevertheless entail biasing information and context that can create problematic expectations and top-down cognitive processes —and the expanded LSU-E provides a way to minimize those as well.

Take, for instance, CSI. Crime scene investigators customarily receive information about the scene even before they arrive to the crime scene itself, such as the presumed manner of death (homicide, suicide, or accident) or other investigative theories (such as an eyewitness account that the burglar entered through the back window, etc.). When the CSI receives such details before actually seeing the crime scene for themselves, they become prone to develop a priori expectations and hypotheses, which can bias their subsequent perception and interpretation of the actual crime scene, and impact if and what evidence they collect. The same applies to other non-comparative forensic domains, such as forensic pathology, fire investigators and digital forensics. For example, telling a fire investigator —before they arrive and examine the fire scene itself— that the property was on the market for two years but did not sell, or/and that the owner had recently insured the property, can bias their work and conclusions.

Combating bias in these domains is especially challenging since these experts need at least some contextual information in order to do their work (unlike, for example, firearms, fingerprint, and DNA experts, who require minimal contextual information to perform comparisons of physical evidence).

The aim of LSU-E is not to deprive experts of the information they need, but rather to minimize bias by providing that information in the optimal sequence. The principle is simple: Always begin with the actual data/evidence —and only that data/evidence— before considering any other contextual information, be it explicit or implicit, reference materials, or any other contextual or meta-information.

In CSI, for example, no contextual information should be provided until after the CSI has initially seen the crime scene for themselves and formed (and documented) their initial impressions, derived solely from the crime scene and nothing else. This allows them to form an initial impression driven only by the actual data/evidence. Then, they can receive relevant contextual information before commencing evidence collection. The goal is clear: As much as practically possible, experts should —at least initially— form their opinion based on the raw data itself before being given any further information that could influence their opinion.

Of course, LSU-E is not limited to forensic work and can be readily applied to many domains of expert decision making. For example, in healthcare, a medical doctor should examine a patient before making a diagnosis (or even generating a hypothesis) based on contextual information. The use of SBAR (Situation, Background, Assessment and Recommendation [49,50]) should not be provided until after they have seen the actual patient. Similarly, workplace safety inspectors should not be made aware of a company’s past violations until after they have evaluated the worksite for themselves without such knowledge [32].

Beyond minimizing bias

Beyond the issue of bias, expert decisions are stronger when they are less noisy and based on the ‘right’ information —the most appropriate, reliable, relevant and diagnostic information. LSU-E provides criteria (described below) for identifying and prioritizing this information. Rather than exposing experts to information in a random or incidental order, LSU-E aims to optimize the sequence of information so as to utilize (or counteract) cognitive and psychological influences (such as, primacy effects, selective attention and confirmation bias; see Section 1.1) and thus empower experts to make better decisions. It is also critical that as the expert progresses through the informational sequence, they document what information they see and any changes in their opinion. This is to ensure that it is transparent what information was used in their decision making and how [51,52].

Criteria for sequencing information in LSU-E

Optimizing the order of information not only minimizes bias but also reduces noise and improves the quality of decision making more generally. The question is: How should one determine what information experts should receive and how best to sequence it? LSU-E provides three criteria for determining the optimal sequence of exposure to task-relevant information: biasing power, objectivity, and relevance —which are elaborated below

1. Biasing power.

The biasing power of relevant information varies drastically. Some information may be strongly biasing, whereas other information is not biasing at all. For example, the technique used to lift and develop a fingerprint is minimally biasing (if at all), but the medication found next to a body may bias the manner-of- death decision. It is therefore suggested that the non- (or less) biasing relevant information be put before the more strongly biasing relevant information in the order of exposure.

2. Objectivity.

Task-relevant information also varies in its objectivity. For example, an eyewitness account of an event is typically less objective than a video recording of the same event —but video re cordings can also vary in their objectivity, depending on their completeness, perspective, quality, etc. It is therefore suggested that the more objective information be put before the less objective in formation in the order of exposure.

3. Relevance.

Some relevant information stands at the very core of the work and necessarily underpins the decision, whereas other relevant information is not as central or essential. For example, in deter mining manner-of-death, the medicine found next to a body would typically be more relevant (for instance, to determine which toxi cological tests to run) than the decedent’s history of depression. It is therefore suggested that the more relevant information is put before the more peripheral information in the order of exposure, and –of course- any information that is totally irrelevant to the decision should be omitted altogether (such as the past criminal history of a suspect).

The above criteria are ‘guiding principles’ because:

A. The suggested criteria above are actually a continuum rather than a simple dichotomy [45,48,53]. One may even consider variability within the same category of information; for example, a higher quality video recording may be considered before a lower quality recording, or a statement from a sober eyewitness may be considered before a statement from an intoxicated witness.

B. The three criteria are not independent; they interact with one another. For example, objectivity and relevance may interact to determine the power of the information (e.g., even highly objective information should be less powerful if its relevance is low, or conversely, highly relevant information should be less powerful if its objectivity is low). Hence, the three criteria are not to be judged in isolation from each other.

C. The order of information needs to be weighed against the potential benefit it can provide [52]. For example, at the trial of police officer Derek Chauvin in relation to the death of George Floyd, the forensic pathologist Andrew Baker testified that he “intentionally chose not” to watch video of Floyd’s death before conducting the autopsy because he “did not want to bias [his] exam by going in with pre conceived notions that might lead [him] down one path or another” [54]. Hence, his decision was to examine the raw data first (an au topsy of the body) before exposure to other information (the video). Such a decision should also consider the potential benefit of watch ing the video before conducting the autopsy, in terms of whether the video might guide the autopsy more than bias it. In other words, LSU-E requires one to consider the potential benefit relative to the potential biasing effect [52].

With this approach, we urge experts to carefully consider how each piece of information satisfies each of these three criteria and whether and when it should, or should not, be included in the sequence —and whenever possible, to document their justification for including (or excluding) any given piece of information. Of course, this raises prac tical questions about how to best implement LSU-E, such as using case managers —and effective implementation strategies may well vary be tween disciplines and/or laboratories— but first we need to acknowl edge these issues and the need to develop approaches to deal with them.

Conclusion

In this paper, we draw upon classic cognitive and psychological research on factors that influence and underpin expert decision making to propose a broad and versatile approach to strengthening expert decision making. Experts from all domains should first form an initial impression based solely on the raw data/evidence, devoid of any reference material or context, even if relevant. Only thereafter can they consider what other information they should receive and in what order based on its objectivity, relevance, and biasing power. It is furthermore essential to transparently document the impact and role of the various pieces of information on the decision making process. As a result of using LSU-E, decisions will not only be more transparent and less noisy, but it will also make sure that the contributions of different pieces of information are justified by, and proportional to, their strength.

Références

[1] S.E. Asche, Forming impressions of personality, J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol., 41 (1964), pp. 258-290

[2] C.I. Hovland (Ed.), The Order of Presentation in Persuasion, Yale University Press (1957)

[3] D. Krane, S. Ford, J. Gilder, K. Inman, A. Jamieson, R. Koppl, et al. Sequential unmasking: a means of minimizing observer effects in forensic DNA interpretation, J. Forensic Sci., 53 (2008), pp. 1006-1107

[4] I.E. Dror, W.C. Thompson, C.A. Meissner, I. Kornfield, D. Krane, M. Saks, et al. Context management toolbox: a Linear Sequential Unmasking (LSU) approach for minimizing cognitive bias in forensic decision making, J. Forensic Sci., 60 (4) (2015), pp. 1111-1112

[5] F.H. Lund. The psychology of belief: IV. The law of primacy in persuasion, J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol., 20 (1925), pp. 183-191

[6] B.B. Murdock Jr. The serial position effect of free recall, J. Exp. Psychol., 64 (5) (1962), p. 482

[7] J. Deese, R.A. Kaufman. Serial effects in recall of unorganized and sequentially organized verbal material, J. Exp. Psychol., 54 (3) (1957), p. 180

[8] J.M. Darley, P.H. Gross. A hypothesis-confirming bias in labeling effects,J. Pers. Soc. Psychol., 44 (1) (1983), pp. 20-33

[9] A. Treisman. Contextual cues in selective listening, Q. J. Exp. Psychol., 12 (1960), pp. 242-248

[10] J. Bargh, E. Morsella. The unconscious mind, Perspect. Psychol. Sci., 3 (1) (2008), pp. 73-79

[11] D.A. Broadbent. Perception and Communication, Pergamon Press, London, England (1958)

[12] J.A. Deutsch, D. Deutsch. Attention: some theoretical considerations, Psychol. Rev., 70 (1963), pp. 80-90

[13] A. Tversky, D. Kahneman. Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases, Science, 185 (4157) (1974), pp. 1124-1131

[14] R.S. Nickerson. Confirmation bias: a ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises, Rev. Gen. Psychol., 2 (1998), pp. 175-220

[15] C. Barry, K. Halfmann. The effect of mindset on decision-making, J. Integrated Soc. Sci., 6 (2016), pp. 49-74

[16] P.C. Wason. On the failure to eliminate hypotheses in a conceptual task, Q. J. Exp. Psychol., 12 (3) (1960), pp. 129-140

[17] B.M. Staw. The escalation of commitment: an update and appraisal, Z. Shapira (Ed.), Organizational Decision Making, Cambridge University Press (1997), pp. 191-215

[18] M. Sherif, D. Taub, C.I. Hovland. Assimilation and contrast effects of anchoring stimuli on judgments, J. Exp. Psychol., 55 (2) (1958), pp. 150-155

[19] C.A. Anderson, M.R. Lepper, L. Ross. Perseverance of social theories: the role of explanation in the persistence of discredited information, J. Pers. Soc. Psychol., 39 (6) (1980), pp. 1037-1049

[20] M.L. Dean. Presentation order effects in product taste tests, J. Psychol., 105 (1) (1980), pp. 107-110

[21] K.A. Carlson, J.E. Russo. Biased interpretation of evidence by mock jurors, J. Exp. Psychol. Appl., 7 (2) (2001), p. 91

[22] R.G. Lawson. Order of presentation as a factor in jury persuasion. Ky, LJ, 56 (1967), p. 523

[23] D. Jolley, K.M. Douglas. Prevention is better than cure: addressing anti-vaccine conspiracy theories, J. Appl. Soc. Psychol., 47 (2017), pp. 459-469

[24] A.R. Klales, K.M. Lesciotto. The “science of science”: examining bias in forensic anthropology, Proceedings of the 68th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences (2016)

[25] M. Davidson, C. Rando, S. Nakhaeizadeh. Cognitive bias and the order of examination on skeletal remains, Proceedings of the 71st Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences (2019)

[26] D. Kahneman, O. Sibony, C. Sunstein. Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment, William Collins (2021)

[27] I.E. Dror. Cognitive and human factors in expert decision making: six fallacies and the eight sources of bias, Anal. Chem., 92 (12) (2020), pp. 7998-8004

[28] J. Kukucka, S.M. Kassin, P.A. Zapf, I.E. Dror. Cognitive bias and blindness: a global survey of forensic science examiners, Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 6 (2017), pp. 452-459

[29] I.E. Dror. The paradox of human expertise: why experts get it wrong, N. Kapur (Ed.), The Paradoxical Brain, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK (2011), pp. 177-188

[30] C. Eeden, C. De Poot, P. Koppen. The forensic confirmation bias: a comparison between experts and novices, J. Forensic Sci., 64 (1) (2019), pp. 120-126

[31] C. Huang, R. Bull. Applying Hierarchy of Expert Performance (HEP) to investigative interview evaluation: strengths, challenges and future directions, Psychiatr. Psychol. Law, 28 (2021)

[32] C. MacLean, I.E. Dror. The effect of contextual information on professional judgment: reliability and biasability of expert workplace safety inspectors,J. Saf. Res., 77 (2021), pp. 13-22

[33] E. Rassin. Anyone who commits such a cruel crime, must be criminally irresponsible’: context effects in forensic psychological assessment, Psychiatr. Psychol. Law (2021)

[34] V. Meterko, G. Cooper. Cognitive biases in criminal case evaluation: a review of the research, J. Police Crim. Psychol. (2021)

[35] C. FitzGerald, S. Hurst. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review, BMC Med. Ethics, 18 (2017), pp. 1-18

[36] M.K. Goyal, N. Kuppermann, S.D. Cleary, S.J. Teach, J.M. Chamberlain. Racial disparities in pain management of children with appendicitis in emergency departments, JAMA Pediatr, 169 (11) (2015), pp. 996-1002

[37] I.E. Dror. Biases in forensic experts, Science, 360 (6386) (2018), p. 243

[38] S.M. Kassin, I.E. Dror, J. Kukucka. The forensic confirmation bias: problems, perspectives, and proposed solutions, Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 2 (1) (2013), pp. 42-52

[39] NAS. National Research Council, Strengthening Forensic Science in the United States: a Path Forward, National Academy of Sciences (2009)

[40] PCAST, President’s Council of Advisors on science and Technology (PCAST), Report to the President – Forensic Science in Criminal Courts: Ensuring Validity of Feature-Comparison Methods, Office of Science and Technology, Washington, DC (2016)

[41] NCFS, National Commission on Forensic Science. Ensuring that Forensic Analysis Is Based upon Task-Relevant Information, National Commission on Forensic Science, Washington, DC (2016)

[42] Forensic Science Regulator. Cognitive bias effects relevant to forensic science examinations, disponible sur https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/914259/217_FSR-G-217_Cognitive_bias_appendix_Issue_2.pdf

[43] ANZPAA, A Review of Contextual Bias in Forensic Science and its Potential Legal Implication, Australia New Zealand Policing Advisory Agency (2010)

[44] J. Kukucka, I.E. Dror. Human factors in forensic science: psychological causes of bias and error, D. DeMatteo, K.C. Scherr (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Psychology and Law, Oxford University Press, New York (2021)

[45] I.E. Dror, J. Melinek, J.L. Arden, J. Kukucka, S. Hawkins, J. Carter, D.S. Atherton. Cognitive bias in forensic pathology decisions, J. Forensic Sci., 66 (4) (2021)

[46] N. Sunde, I.E. Dror. A hierarchy of expert performance (HEP) applied to digital forensics: reliability and biasability in digital forensics decision making, Forensic Sci. Int.: Digit. Invest., 37 (2021)

[47] D.C. Murrie, M.T. Boccaccini, L.A. Guarnera, K.A. Rufino. Are forensic experts biased by the side that retained them? Psychol. Sci., 24 (10) (2013), pp. 1889-1897

[48] G. Langenburg. Addressing potential observer effects in forensic science: a perspective from a forensic scientist who uses linear sequential unmasking techniques, Aust. J. Forensic Sci., 49 (2017), pp. 548-563

[49] C.M. Thomas, E. Bertram, D. Johnson. The SBAR communication technique, Nurse Educat., 34 (4) (2009), pp. 176-180

[50] I. Wacogne, V. Diwakar. Handover and note-keeping: the SBAR approach, Clin. Risk, 16 (5) (2010), pp. 173-175

[51] M.A. Almazrouei, I.E. Dror, R. Morgan. The forensic disclosure model: what should be disclosed to, and by, forensic experts?, International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 59 (2019)

[52] I.E. Dror. Combating bias: the next step in fighting cognitive and psychological contamination, J. Forensic Sci., 57 (1) (2012), pp. 276-277

[53] D. Simon, Minimizing Error and Bias in Death Investigations, vol. 49, Seton Hall Law Rev. (2018), pp. 255-305

[54] CNN. Medical examiner: I “intentionally chose not” to view videos of Floyd’s death before conducting autopsy, April 9, 2021, disponible sur https://edition.cnn.com/us/live-news/derek-chauvin-trial-04-09-21/h_03cda59afac6532a0fb8ed48244e44a0 (2011)