Difficult disappearances to solve

Every year in France, nearly 40,000 people are reported missing. In 2022, the association ARPD recorded 60,000 “worrying disappearances”, including 43,200 minors; around 1,000 cases remain unsolved in practice [1,2]. Over time, the likelihood of finding a missing person—alive or even just their remains—drops drastically. The dense vegetation of undergrowth and forests becomes a major obstacle, rendering both aerial observation and the scent-tracking abilities of search dogs ineffective [3]. In France’s overseas territories, such as Martinique, disappearances are also numerous, and the topography of key disappearance zones is a serious impediment to ground searches and the use of more conventional methods to locate missing persons [4,5]. Drone pilots from the French Gendarmerie are often called in, but the drones currently used are only equipped with optical sensors, which struggle to detect anything beneath the vegetation cover. Nevertheless, drones remain valuable for rescue missions: in the United States, they are widely used to locate accident victims in the wild, deliver communication devices, medication, or supplies [6–8]. When dense canopy and vegetation make traditional searches ineffective, an alternative becomes necessary: LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging). Already proven in many fields, including archaeology, LiDAR could bring real added value to judicial investigations in forest environments [9–11].

The promise of LiDAR

A LiDAR sensor emits up to 240,000 laser pulses per second. It measures the time taken for each beam to return to the emitter after hitting an obstacle, reconstructing a 3D point cloud [12]. Even though a large percentage of the beams bounce off leaves, the remainder reaches the ground and maps its relief. Investigators can select a precise height range—for example, between 15 and 50 cm above ground level—which effectively removes the canopy. This filtering provides access to the volumes present. A body or object can thus stand out from the natural relief [13].

A full-scale test in Isère

In April 2024, a team made up of a forensic anthropologist and a LiDAR drone specialist placed a volunteer lying down in a thicket in Montbonnot-Saint-Martin (Isère) to test whether a human body could produce a detectable signature despite dense vegetation. The test area, 0.8 hectares in size, contained 721 trees per hectare and showed a Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) between +0.6 and +1, proof of an exceptionally thick canopy [13–15].

Two LiDAR sensors

| Sensor (DJI) | Max choes/point | Flight speed | % of “ground” points | Verdict |

| Zenmuse L1 | 3 | 1,9 m/s | 0,11 % | The body is barely detectable |

| Zenmuse L2 | 5 | 2 m/s | 0,26 % | Silhouette detected in just a few clicks |

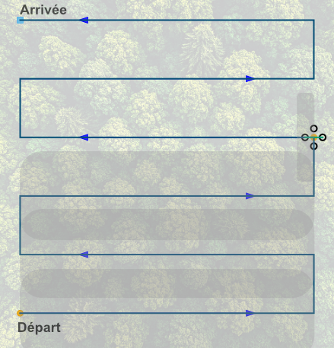

Much like a GPS (Global Positioning System), the drone’s remote-control screen provides a zenith view of the search area. When a mission is programmed, a zone is defined, and the drone’s software plots the route it must follow. The drone flies in a straight line, then upon reaching the edge of the zone, it performs a 90° turn, advances, makes another 90° turn, and continues in the opposite direction. As the drone retraces its path, the LiDAR beam overlaps the previous pass, enabling greater data acquisition both above and beneath the canopy (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Schematic representation of a drone’s flight path. The grey bands represent the areas scanned by the LiDAR. The dark grey zones show the overlap of the laser beam occurring with each drone pass.

The test demonstrates that, even under a dense canopy, a next-generation LiDAR can capture enough ground points to detect a body on the surface.

After a 7-minute flight, the data are imported into DJI Terra Pro and then TerraSolid. Filtering at the 0.15–0.50 m height slice highlights a characteristic over-density at the volunteer’s location. Comparison with a control scan without a body makes it possible to distinguish natural anomalies (rocks, stumps) and to prepare a true/false positive matrix to assess the statistical robustness of the detection.

Weather and regulations: field limitations

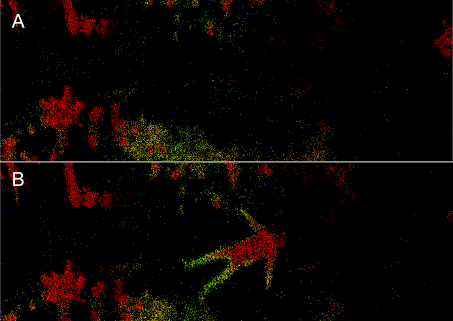

The test demonstrates that, even under dense canopy, a next-generation LiDAR can capture enough ground points to detect a body on the surface (Figure 2). Selecting an appropriate height band is crucial to reduce noise from rocks or tree trunks. However, weather conditions (rain, fog, wind > 30 km/h) remain limiting factors, as do drone autonomy and regulatory distance constraints.

Figure 2: A: acquisition without a body on the ground, B: acquisition with the volunteer placed on the ground.

The aim is to evaluate up to which degree of decomposition bodies still leave a detectable LiDAR signature.

What’s next?

Airborne LiDAR offers a non-destructive tool to locate human remains under vegetation and to document the three-dimensional topography of a scene prior to any excavation, ensuring safe access to the body. Its rapid deployment (lightweight equipment, one to two operators) provides a cheaper and safer alternative to human search parties or helicopter flights in difficult terrain.

Initially, research is focused on the detection of living volunteers, but for cases where individuals are presumed deceased, tests will need to be carried out on decomposing bodies. The aim is to evaluate up to which degree of decomposition a body still leaves a detectable LiDAR signature. Such research cannot currently take place in France, so collaborations with foreign laboratories are being considered. Another possibility would be to complement LiDAR with other sensors, such as thermal imaging or multispectral sensors. Thermal imaging could detect heat sources linked to entomological activity on the body [16], while multispectral sensors could reveal chemical changes in soil or vegetation over time associated with decomposition [17,18].

In just a few hours, a simple raw point cloud can be transformed into a priority search zone.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that even a tiny percentage of “ground points” can be enough to reveal the presence of a body in vegetation usually considered impenetrable. In just a few hours, a raw point cloud can be transformed into a priority search zone, reducing both the scope of the search and the anxious waiting of families. These results still need to be confirmed in other forest types and with actual donors, but LiDAR is already breaking through the opacity of disappearances.

The results confirm that airborne LiDAR sensors are capable of highlighting the presence of a body in heavily vegetated environments. In the densest conditions, the ground point density reached 0.26%. The study underlines the need to improve post-processing techniques, particularly the selection of cloud points and the development of true/false positive analyses, in order to optimize detection reliability. Finally, the integration of complementary sensors, such as thermal or multispectral devices, appears to be a promising avenue for identifying more precisely the thermal anomalies and chemical markers associated with decomposition.

References

[1] ARPD | ARPD, (n.d.). https://www.arpd.fr/fr (accessed February 28, 2024).

[2] M. de l’Intérieur, Disparitions inquiétantes, http://www.interieur.gouv.fr/Archives/Archives-des-dossiers/2015-Dossiers/L-OCRVP-au-caeur-des-tenebres/Disparitions-inquietantes (accessed April 17, 2024).

[3] U. Pietsch, G. Strapazzon, D. Ambühl, V. Lischke, S. Rauch, J. Knapp, Challenges of helicopter mountain rescue missions by human external cargo: Need for physicians onsite and comprehensive training, Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine 27 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049-019-0598-2.

[4] C. Gratien, La mort de Benoit Lagrée officiellement reconnue, Martinique La 1ère (n.d.).

[5] Disparition de Marion à la Dominique : où en sont les recherches ?, guadeloupe.franceantilles.fr (2024). https://www.guadeloupe.franceantilles.fr/actualite/faits-divers/disparition-de-marion-a-la-dominique-ou-en-sont-les-recherches-976553.php (accessed October 25, 2024).

[6] C. Van Tilburg, First Report of Using Portable Unmanned Aircraft Systems (Drones) for Search and Rescue, Wilderness & Environmental Medicine 28 (2017) 116–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wem.2016.12.010.

[7] Y. Karaca, M. Cicek, O. Tatli, A. Sahin, S. Pasli, M.F. Beser, S. Turedi, The potential use of unmanned aircraft systems (drones) in mountain search and rescue operations, The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 36 (2018) 583–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2017.09.025.

[8] H.B. Abrahamsen, A remotely piloted aircraft system in major incident management: Concept and pilot, feasibility study, BMC Emergency Medicine 15 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-015-0036-3.

[9] J.C. Fernandez-Diaz, W.E. Carter, R.L. Shrestha, C.L. Glennie, Now You See It… Now You Don’t: Understanding Airborne Mapping LiDAR Collection and Data Product Generation for Archaeological Research in Mesoamerica, Remote Sensing 6 (2014) 9951–10001. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs6109951.

[10] T.S. Hare, M.A. Masson, B. Russell, High-Density LiDAR Mapping of the Ancient City of Mayapán, Remote. Sens. 6 (2014) 9064–9085.

[11] N.E. Mohd Sabri, M.K. Chainchel Singh, M.S. Mahmood, L.S. Khoo, M.Y.P. Mohd Yusof, C.C. Heo, M.D. Muhammad Nasir, H. Nawawi, A scoping review on drone technology applications in forensic science, SN Appl. Sci. 5 (2023) 233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-023-05450-4.

[12] Zenmuse L2, DJI (n.d.). https://enterprise.dji.com.

[13] P. Nègre, K. Mahé, J. Cornacchini, Unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) paired with LiDAR sensor to detect bodies on surface under vegetation cover: Preliminary test, Forensic Science International 369 (2025) 112411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2025.112411.

[14] S. Li, L. Xu, Y. Jing, H. Yin, X. Li, X. Guan, High-quality vegetation index product generation: A review of NDVI time series reconstruction techniques, International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 105 (2021) 102640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2021.102640.

[15] Z. Davis, L. Nesbitt, M. Guhn, M. van den Bosch, Assessing changes in urban vegetation using Normalised Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) for epidemiological studies, Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 88 (2023) 128080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2023.128080.

[16] J. Amendt, S. Rodner, C.-P. Schuch, H. Sprenger, L. Weidlich, F. Reckel, Helicopter thermal imaging for detecting insect infested cadavers, Science & Justice 57 (2017) 366–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scijus.2017.04.008.

[17] J. Link, D. Senner, W. Claupein, Developing and evaluating an aerial sensor platform (ASP) to collect multispectral data for deriving management decisions in precision farming, Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 94 (2013) 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2013.03.003.

[18] R.M. Turner, M.M. MacLaughlin, S.R. Iverson, Identifying and mapping potentially adverse discontinuities in underground excavations using thermal and multispectral UAV imagery, Engineering Geology 266 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2019.105470.