The clinical and judicial assessment of children who are victims of sexual abuse requires an in-depth understanding of child development and of the manifestations of post-traumatic symptoms that are typical of childhood and adolescence. Recognizing the specific symptom patterns in children makes it possible to distinguish traumatic manifestations from normal developmental variations, within an approach that must necessarily respect the child’s world.

Respecting and building upon the child’s world

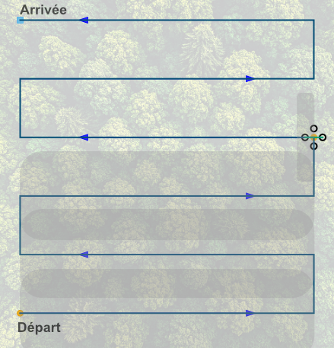

Working with children involves using mediating tools that correspond to their developmental world, employing language and tone appropriate to their age, and exploring their personal interests. Beyond the therapeutic alliance that this fosters, a child’s interests also serve as indicators of their developmental level, environment, and daily organization. These are valuable cues for forensic evaluation.

For instance, consider an 8-year-old child in second grade who, when simply asked about his favorite activities, mentions playing a Paddington game on a tablet. When gently questioned about the tablet and the game, through prompts such as “What do you like about this game?” or “Can you tell me more about this tablet?”, the child explains that the tablet belongs to his father, that he does not have one of his own, and that he is allowed to play on it on Wednesdays and weekends for 30 minutes in the family living room. He says he likes the little bear for his adventures, and is then asked to describe one of his favorite moments.

Respecting the child’s world means striving to avoid the risk of retraumatization during the forensic examination.

The child’s responses allow the evaluator to assess several aspects: an interest and activity consistent with their developmental age, a family framework appropriate for their age regarding screen use, and the child’s ability to construct a narrative (use of pronouns and tenses, spatial and chronological structuring, distinction between imagination and reality, etc.). The interpretation will naturally differ if the child plays a game such as Call of Duty, a war-themed game, rated 16+ or 18+ depending on the version, if the 8-year-old has a screen in their bedroom, or if the subject is instead a 15-year-old adolescent.

Finally, and in my view, most importantly, respecting the child’s world means striving to prevent the risk of retraumatization during the forensic examination. Creating an environment that signals to children they are welcome is essential: children’s books in the waiting area, toys, comfortable seating, and the freedom to move around. Advising caregivers to bring a comfort object or soft toy (doudou) is also important. Returning to the question of post-traumatic symptomatology in children, this issue takes on a particular resonance in light of recent cases such as that of Joël Le Scouarnec, in which 299 identified victims exhibited significant post-traumatic symptoms despite an apparent absence of conscious memories of the assaults committed under anesthesia.

The theoretical framework of sexual psychotrauma

The psyche refers to the entirety of conscious and unconscious mental phenomena: cognitive processes (thought, memory, perception), affective processes (emotions, feelings), psychological defense mechanisms, fantasy and imaginative activity, and personality structures. A traumatic event represents a violent intrusion into the psyche, exceeding the mental apparatus’s capacity for processing and integration what is referred to as traumatic breach (effraction traumatique).

A child who has been sexually abused often remains in denial for a long time

Traumatic breach in a child who has been sexually assaulted presents particular characteristics. Louis Crocq (1999) defines psychotrauma as “a phenomenon involving a breach of the psyche and the overwhelming of its defenses by violent stimuli linked to the occurrence of an event that is aggressive or threatening to the life or integrity (physical or psychological) of an individual who is exposed to it as a victim, witness, or actor.” In cases of sexual assault, this breach takes on a dimension that is beyond the child’s psychological comprehension. As Tardy (2015) points out, “A child who has been abused often remains in denial for a long time, a defense mechanism aimed at avoiding the realization that the adults supposed to protect them were, in fact, the aggressors, which would be too distressing to acknowledge.”

The repetition syndrome, as described by Crocq (2004), is defined as “a set of clinical manifestations through which the traumatized patient involuntarily and repeatedly relives their traumatic experience with great intensity.” Thus, in children and adolescents, as in adults, numerous symptoms related to repetition or avoidance of repetition can be observed.

Age-specific symptoms: a developmental approach

Traumatic manifestations in younger children:

They are characterized by poorly integrated intrusive recollections, consisting mainly of intense sensations and emotions, as described by Eth and Pynoos (1985) and by Pynoos, Steinberg et al. (1995). Beyond ordinary childhood play, specific play behaviors linked to the traumatic event may emerge. These post-traumatic play patterns represent a major clinical indicator. Fletcher (1996) describes them as “repetitive, involving a central element connected, or sometimes not connected, to the event, less elaborate and imaginative than typical play, generally emotionally charged (anxiety), rigid, and joyless.” Such play loses its normal creative and exploratory function, becoming compulsive and stereotyped.

Neurovegetative hyperarousal and avoidance are common post-traumatic symptoms. In children, they manifest as anxious hypervigilance, exaggerated startle responses, and sleep disturbances with frequent awakenings. Avoidance may take the form of social withdrawal, emotional numbing, and developmental regression affecting toilet training, sleep, or the reemergence of early childhood fears. In his longitudinal study of 166 sexually abused children, Putnam (2003) found that 40% developed hyperactivity symptoms within six months following disclosure, compared to 8% in the general population. The author interprets this hyperactivity as an adaptive flight response to intrusive post-traumatic stimuli.

Some children develop overly smooth, inconspicuous behaviors that draw no attention at all.

Post-traumatic manifestations in children often display little-known specificities that make their identification particularly complex. Unlike adults, children frequently present with nonspecific symptoms according to developmental research, especially younger children (under six years old).

From the earliest age, disturbances in body awareness and bodily experience constitute a key clinical marker: restriction in clothing choices or adoption of sexualized clothing, extreme washing behaviors, difficulties with nudity, poor bodily investment, a devalued image of their body or of certain body parts, disturbances in tactile relationships, and avoidance of affectionate gestures. These bodily manifestations often go unrecognized because they may appear trivial or be attributed to other causes. In contrast to the agitation sometimes observed, some children develop overly smooth, inconspicuous behaviors that draw no attention at all. This inhibited presentation, characterized by excessive compliance and extreme conformity, paradoxically constitutes a warning sign. Research emphasizes the importance of “keeping in mind that some of these behaviors are common in this age group. Thus, symptoms of neurovegetative hyperarousal are expressed more as an intensification of behaviors already present in the child, sometimes difficult for significant others to notice” (Eth & Pynoos, 1985; Pappagallo, Silva & Rojas, 2004).

Older children (6 to 12 years old):

In addition to the previously described symptoms, children in this age group may present somatic complaints (headaches, abdominal pain, etc.) which, due to their nonspecific nature, are not always associated with sexual trauma. Nevertheless, these somatic manifestations are important clinical indicators within a comprehensive assessment.

In school-aged children, intrusive memories become more structured but may include protective cognitive distortions that minimize the severity of the event. Post-traumatic play also evolves: it becomes “more elaborate and sophisticated, involving transformation of certain aspects of the event, the introduction of symbolic dangers (monsters), and the inclusion of other people (peers)” (Fletcher, 1996). These transformations reflect an attempt at more mature psychological processing. School functioning often becomes significantly affected, with attention difficulties, declining academic performance, anxiety-related school refusal, as well as diminished self-esteem and reduced trust in caregivers. Frequent somatic symptoms may also lead to school absenteeism.

Adolescence :

Drawings and post-traumatic play become rare, replaced by other modes of expressing distress. Manifestations resemble those observed in adults (Yule, 2001; Rojas & Lee, 2004), with recurrent memories, flashbacks, and pronounced emotional numbing, that is, a marked reduction in the intensity and range of emotional expression. Emotional numbing manifests through diminished or fixed facial expressions, a monotone voice, dull or inexpressive eyes, inappropriate or absent emotional responses, and a reduced capacity to feel joy, sadness, or anger. It may lead to difficulties forming emotional bonds, impoverished interpersonal relationships, and an impression of “coldness” perceived by others. Addictive behaviors may emerge, involving either substances (alcohol, drugs, toxic products) or activities (video games, pornography, sexual behaviors, gambling), along with risk-taking behaviors (speeding, dangerous stunts, delinquent acts).

The assessment must distinguish between normal sexual exploration and pathological manifestations.

Specific symptoms of sexual trauma

Disturbances in body awareness and bodily experience are characteristic and represent a specific marker of physical and sexual trauma. Overall, the sexualization of language and behaviors is a strong indicator, particularly when the change appears suddenly.

Problematic Sexual Behaviors (PSB) represent a specific manifestation that is especially important to identify. According to the ATSA (Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers), PSB are defined as “sexual behaviors displayed by a child that are considered inappropriate for their age or level of development” and that may be “harmful to the child themselves or to other children involved.”

PSB are defined in children up to age 12, and their assessment requires a solid understanding of child and adolescent sexual development, as well as the use of age-appropriate language. This definition follows a developmental approach in which assessment must distinguish normal sexual exploration from pathological manifestations. According to Chaffin et al. (2006), sexual behaviors are considered problematic when they meet one or more of the following six criteria: they occur with “high frequency or intensity,” “interfere with the child’s social or cognitive development,” “involve force, coercion, or intimidation,” are “associated with physical injury or emotional distress,” “occur between children of different developmental stages,” and “persist despite adult intervention.” PSB may include sexual touching of other children, excessive masturbation, sexual knowledge that is inappropriate for the child’s developmental stage, or hypersexualized behaviors.

Symptoms in adulthood:

Longitudinal studies demonstrate the persistence of symptoms into adulthood. A British study of 2,232 18-year-old participants revealed an increased risk of psychiatric disorders: 29.2% presented with major depression, 22.9% with conduct disorders, 15.9% with alcohol dependence, 8.3% with self-harming behaviors, and 6.6% with suicide attempts.

The impact on intimate and marital life is particularly well documented. According to Gérard (2014), nearly 60% of adults who were sexually abused in childhood experience relationship isolation, and 20% have never been able to form a long-term partnership. Relational difficulties are characterized by a paradoxical oscillation between excessive mistrust and dependence, polymorphic sexual disturbances (“hypersexuality or lack of libido, absence of pleasure, pain, risky sexual behaviors”), and the search for a “repairing” partner that often leads to intense frustration. Among women, specific menstrual disturbances are frequently reported from puberty onward: irregularities, pain, amenorrhea, and feelings of disgust.

In forensic evaluations of adults who were sexually abused as children, many of the same symptoms observed in childhood may reappear: persistent masturbatory behaviors originating around the time of the abuse or its disclosure, avoidant somatizations, and attention difficulties. Collecting these clinical indicators can help establish coherence with the events described in the context of psychological expertise. Moreover, for the victim, such analysis can provide meaning to behaviors that were previously misunderstood or socially disapproved of.

It is not necessary to remember in order to suffer from post-traumatic symptoms

The Scouarnec case: symptoms without memory

The Scouarnec case illustrates perfectly the issue of post-traumatic symptoms in the absence of conscious memory. The 299 identified victims, mostly minors who were assaulted under anesthesia, exhibited symptomatic manifestations even before the facts were revealed by investigators. Amélie Lévêque testified: “I actually had so many aftereffects from that operation that were there, but no one could explain them.” These sequelae included medical phobias, eating disorders, and “the diffuse feeling that something abnormal had happened.” Expert witnesses at the trial confirmed that “it is not necessary to remember in order to suffer from post-traumatic symptoms.

Jean-Marc Ben Kemoun, child psychiatrist and forensic doctor, explains this phenomenon as the “memory of the body”: “The body speaks, and the less we are consciously aware of a painful or stressful event, the stronger its impact on the body.” Even in an altered state of consciousness, the traumatic impact persists, generating long-lasting symptoms in the absence of explicit memory.

Clinical implications and perspectives

This clinical reality underscores the importance of a multidimensional assessment that respects developmental particularities. Forensic evaluation must include the observation of play and interests according to age, assessment of social and academic adjustment, and evaluation of the individual’s ability to project themselves positively into the future. The Scouarnec case demonstrates that the absence of conscious memories in no way excludes the existence of trauma and its lasting consequences. This understanding is essential for a symptom-based clinical assessment, particularly in young children or in individuals who experienced sexual trauma before the age of six.

Bibliographie :

Crocq, L. (2004). Traumatismes psychiques : Prise en charge psychologique des victimes. Paris : Masson.

Tardy, M.-N. (2015). Chapitre 8. Vécu de l’enfant abusé sexuellement. Dans M.-N. Tardy (dir.), La maltraitance envers les enfants. Les protéger des méchants (pp. 123-150). Paris : Odile Jacob.

Drell, M. J., Siegel, C. H., Gaensbauer, T. J. (1993). Post-traumatic stress disorder. Dans C. H. Zeanah (dir.), Handbook of infant mental health (pp. 291-304). New York : Guilford Press.

Fletcher, K. E. (1996). Childhood posttraumatic stress disorder. Dans E. J. Mash & R. A. Barkley (dir.), Child psychopathology (pp. 242-276). New York : Guilford Press.

Frank W. Putnam, Ten-Year Research Update Review: Child Sexual Abuse, Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, Volume 42, Issue 3, 2003, Pages 269-278,

Pynoos, R. S., Steinberg, A. M., Wraith, R. (1995). A developmental model of childhood traumatic stress. Dans D. Cicchetti & D. J. Cohen (dir.), Developmental psychopathology (Vol. 2, pp. 72-95). New York : Wiley.

Scheeringa, M. S., Zeanah, C. H. (2003). Symptom expression and trauma variables in children under 48 months of age. Infant Mental Health Journal, 24(2), 95-105.

Yule, W. (2001). Post-traumatic stress disorder in the general population and in children. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 62(17), 23-28.

Gérard, C. (2014). Conséquences d’un abus sexuel vécu dans l’enfance sur la vie conjugale des victimes à l’âge adulte. Carnet de notes sur les maltraitances infantiles, 3, 42-48. DOI : 10.3917/cnmi.132.0042

Chaffin, M., Letourneau, E., Silovsky, J. F. (2002). Adults, adolescents, and children who sexually abuse children: A developmental perspective. Dans J. E. B. Myers, L. Berliner, J. Briere, C. T. Hendrix, C. Jenny, & T. A. Reid (dir.), The APEAC handbook on child maltreatment (2e éd., pp. 205-232). Thousand Oaks, CA : Sage.

Chaffin, M., Berliner, L., Block, R., Johnson, T. C., Friedrich, W. N., Louis, D. G., … & Silovsky, J. F. (2006). Report of the ATSA task force on children with sexual behavior problems. Child Maltreatment, 11(2), 199-218.

Gury, M.-A. (2021). Pratique de l’expertise psychologique avec des enfants dans le cadre judiciaire pénal. Psychologues et Psychologies, 273, 24-26.

France Info (6 mars 2025). Procès de Joël Le Scouarnec : une affaire “entrée par effraction” dans la vie de nombreuses victimes, sans souvenirs d’actes subis sous anesthésie.

France 3 Bretagne (14 avril 2025). Procès le Scouarnec : “même sans souvenirs, on peut souffrir de troubles post-traumatiques”. consultable ici.

Pôle fédératif de recherche et de formation en santé publique Bourgogne Franche-Comté (2025). Aide au diagnostic et au repérage ajusté du comportement sexuel problématique chez l’enfant. Projet de recherche AIDAO-CSP.