The ear exhibits such morphological variability that the trace it leaves at a crime scene can become a decisive element of identification. The presence of an earprint can characterize a particular modus operandi, such as attentive listening through the door of a burglarized apartment. Although an earprint alone cannot suffice to identify an individual, its examination represents an undeniable investigative tool.

Introduction

Due to its many variations in size and shape, the ear has always been regarded as a key feature in personal identification. Whether in the work of Rodolphe Archibald Reiss, founder of the first school of forensic science in Lausanne in 1909, or Edmond Locard, who established the first forensic science laboratory in Lyon in 1910, for more than a century, identification specialists have characterized the external auricle as the most distinctive feature of the human face. According to these experts, the ear is so morphologically diverse that no two ears appear identical when examined under standardized photographic conditions. It was in fact Alphonse Bertillon, founder of the anthropometric identification service in Paris in 1882, who first incorporated the ear as a discriminating feature in his “portrait parlé” system for the identification of recidivists.

Recent scientific studies exploring the morphological variability of the ear have demonstrated that, beyond the simple left/right symmetry inversion, this feature alone can make it possible to distinguish between the two ears of the same individual, and even between monozygotic twins. The ear’s high morphological variability means that the trace it leaves at a crime scene can constitute a powerful element of identification. As we shall discuss in more detail below, earprints carry less informational richness than standardized signaletic photographs1, yet they nevertheless exhibit shapes that can be compared and provide a non-negligible associative value.

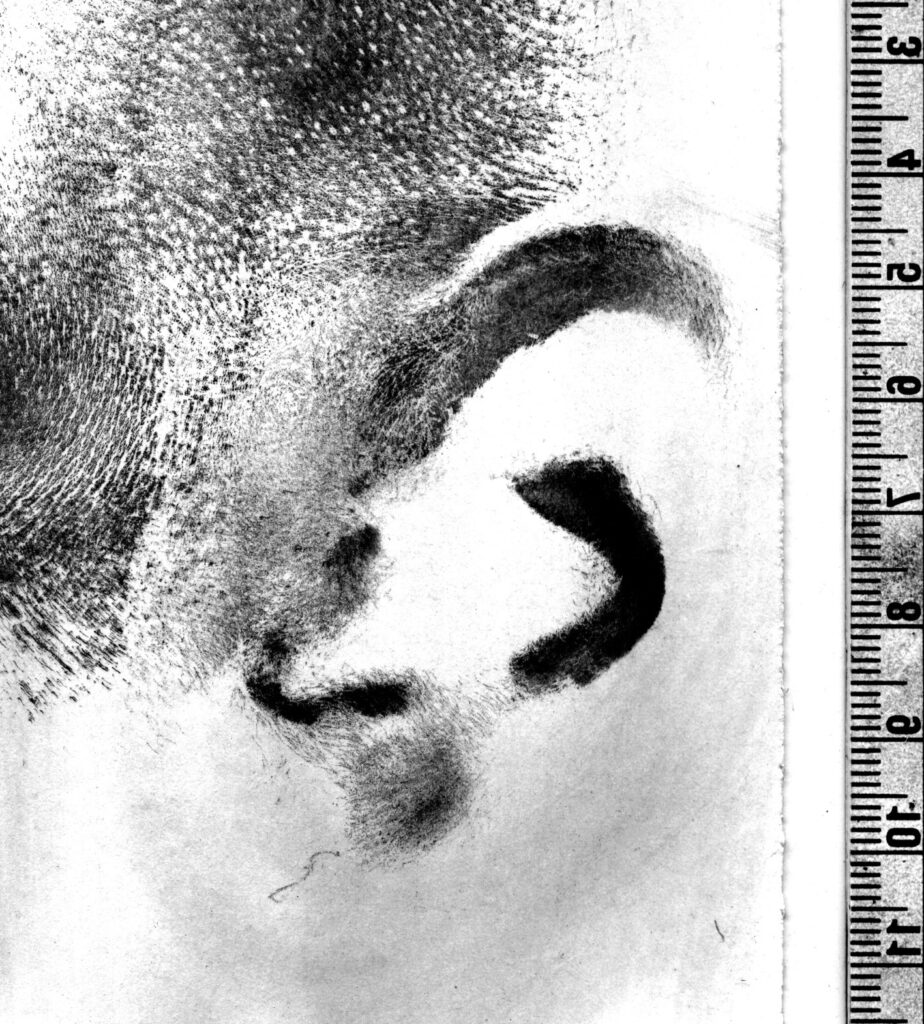

Individual engaged in attentive listening through the door of an apartment. By doing so, the person leaves an earprint that can be exploited by forensic investigators at the crime scene. Sébastien AGUILAR ©

Where are they found?

From a physical perspective, when the ear comes into contact with a surface such as a door, a window, or even a wall, it transfers a thin layer of greasy residues onto the surface. In a way, it is comparable to a stamp-like impression of the ear’s shape left on the support. In burglary cases, offenders often leave an earprint on the door of the targeted apartment as they attempt to determine, by listening, whether anyone is inside. Such traces are collected at crime scenes by forensic police and gendarmerie personnel, both on the doors of burglarized apartments and on landing doors. It is not uncommon for certain individuals, or sometimes groups, to perform multiple listening attempts before committing an offense. Frequently, burglary scenes reveal three or four earprints from different individuals, either on the same floor or on different levels of a building. When burglaries are committed in series, these traces can serve to establish links between cases.

The investigative value of earprints

At a time when the discovery of latent fingerprints at crime scenes is becoming increasingly rare, earprints offer a genuine opportunity for criminal investigation. French, Swiss, and Belgian practices have shown that such traces are far from marginal, as they can be recovered in roughly 20% of residential burglary cases. Offenders tend to be cautious once inside the targeted premises, but they are generally less wary of leaving traces outside the scene of the offense.

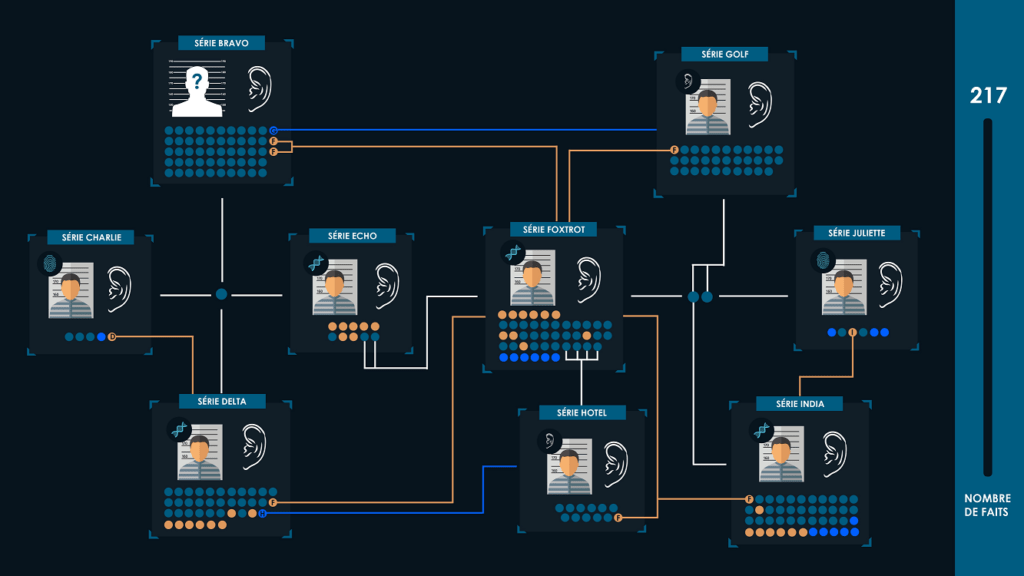

The strength of earprints lies in the fact that they do not require access to a nominal database. The earprint examiner may be able to link several cases together, a process referred to as linkage analysis. Based on these findings, the specialist informs the investigating service of the serial nature of the incidents. The judicial police officer in charge of the investigation can then cross-reference these findings with other forensic evidence, such as latent fingerprints or DNA, in order to identify potential suspects. It is therefore essential that crime scene technicians perform biological sampling near the ear area, particularly on the cheek trace adjacent to the earprint. Recent results indicate that such DNA sampling yields genetic profiles in approximately 25% of cases.

Once these samples are collected, the judicial police officer or investigating magistrate may order the recording of earprints from a suspect against whom there are reasonable grounds to believe that they have committed or attempted to commit the offense. In parallel, the judicial authority may request that a forensic earprint specialist compare the questioned traces with the earprints of the suspect(s).

In a criminal case in the greater Paris area, a suspect was implicated by DNA recovered from bindings used to tie a victim at their home. The suspect explained the presence of his DNA by claiming that he may have touched the bindings at some point in his life, but denied any involvement in the events or even being present at the scene. He related that the bindings had likely been stolen from his own home. However, crime scene technicians also recovered an earprint on the victim’s apartment door. At the request of the judicial police officer, a comparison was conducted between the incriminated trace and the suspect’s earprints. The results of the forensic examination contradicted the suspect’s statements. He found it far more difficult to justify the presence of an earprint corresponding to his own, in addition to his DNA, at the crime scene. In this case, the earprint formed part of a converging body of evidence and allowed investigators to reconstruct a sequence of activities more directly than the DNA trace alone. Unlike DNA, which can be transferred through multiple mechanisms, the earprint is directly tied to the act of listening.

Can an individual’s earprints be recorded?

In accordance with Article 55-1 of the French Code of Criminal Procedure, a judicial police officer may, either directly or under his supervision, carry out external sampling operations on any person likely to provide information about the facts in question, or on any person against whom there are one or more reasonable grounds to suspect that they have committed or attempted to commit the offense. These operations are conducted to obtain the external samples necessary for technical and scientific examinations intended to be compared with traces and evidence collected in the course of the investigation.

The French Constitutional Council ruled, with regard to Article 30 of the Law of March 18, 2003 on Internal Security, that “the expression ‘external sampling’ refers to a procedure that does not involve any internal bodily intervention; it will therefore entail no painful, intrusive, or degrading procedure; the claim of a violation of the inviolability of the human body is therefore unfounded; furthermore, external sampling does not affect the individual’s personal liberty.” Consequently, the recording of earprints may be requested by judicial authorities, and refusal to comply may be punishable by up to one year of imprisonment and a fine of €15,000.

L’admissibilité de la preuve

As in the Anglo-American legal system, where in the United States scientific evidence presented in court is subject to admissibility rules (as established by the Frye or Daubertstandards), the principle of free admissibility of evidence and free judicial assessment prevails in France (Article 427 of the French Code of Criminal Procedure). Thus, the judge is free to accept or reject a piece of evidence according to personal conviction. Consequently, in the search for traces and clues at a crime scene, all forms of evidence are admissible as long as they are obtained legally. The judicial police officer, or any authorized person acting under their supervision, cannot disregard this mode of proof. The earprint, as material evidence, helps characterize a specific modus operandi involving attentive listening through a surface. In many cases, this modus operandi may be indicative of a preparatory act preceding the commission of an offense. In all circumstances, earprints, which may contribute to establishing the truth, should be systematically sought and collected at all crime and misdemeanor scenes.

How should these technical findings be regarded?

In carrying out their examination, the specialist must rely on scientific articles recognized by the scientific community, while also drawing on their professional knowledge and technical expertise acquired through practice and casework.

However, there are often disproportionate expectations in the requests addressed to forensic specialists. Frequently, scientists are asked to provide categorical, almost binary results to the judicial authority regarding the analyses or technical comparisons performed. The following questions, extracted from expert mandates, illustrate the expectation of definitive answers:

• Is the suspect the source of the DNA contact trace discovered on the weapon?

• Was the projectile recovered at the crime scene fired by the seized weapon—yes or no?

• Was the earprint found on the door left by Mr. X or not?

Since the early 2000s, the rise of television series such as the well-known CSI: Crime Scene Investigation has had a considerable impact on how forensic science is perceived by the general public and judicial actors alike. While these series have sparked genuine interest in a previously little-known profession, they have also propagated the idea that science can provide absolute, factual proof, leaving no room for uncertainty.

Scientific advances in criminal sciences in recent years have undoubtedly been spectacular. Today, it is possible to establish a genetic profile from just a few cells, a technique that would have been unimaginable merely fifteen years ago. As forensic methods and technologies become increasingly sensitive and specific, operators and analysts must pay even greater attention to the potential risks of error, contamination, transfer, or misinterpretation. In forensic science, correspondence between two elements is never absolute, and the same holds true for earprints. When comparing two traces originating from the same source, some differences will always be observed. Similarly, when comparing traces with earprints from individuals who are not their source, there is always the possibility of observing a coincidental match. The scientist’s task is therefore to adopt a methodology that allows for the control and characterization of these risks of error. This is the central challenge of forensic science, and particularly of forensic police work. Thus, in the case of earprints, as in all areas of forensic science, it is not reasonable to expect certainties. At best, the findings can be expressed in probabilistic terms.

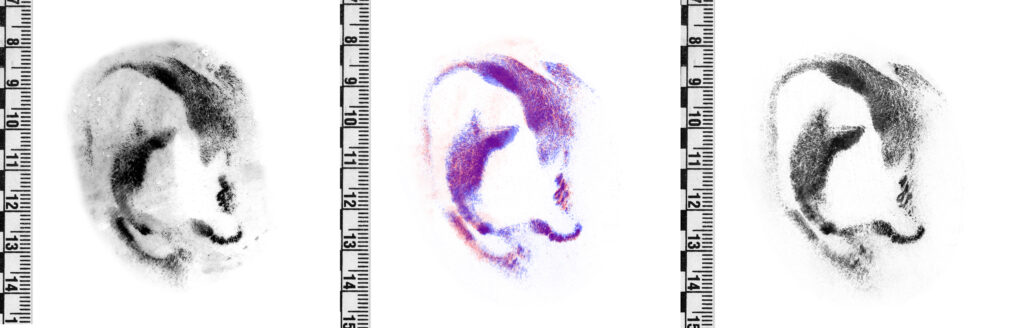

In earprint examination, it is essential that the specialist be able to assess the morphological structure of the individual’s ear. Since the ear consists of both cartilaginous and more flexible parts, the methodology must necessarily account for the organ’s intrinsic variability. By recording multiple impressions of the same ear, the specialist evaluates the observed differences (distortion, flattening, absence, deformation, etc.). This process enables the analysis, comparison, and assessment of the reproducibility of each ear feature present in the earprints, and forms the basis for what is known as intravariability.

Accordingly, when the specialist compares a questioned trace with an individual’s earprint, they assess, on the one hand, the differences encountered in relation to the previously defined intravariability, and on the other hand, the degree of rarity of each observable feature (linked to intervariability). If the differences are limited in number and fall within the defined tolerance zone, the specialist may establish a more or less strong association depending on the quality of the trace and the number of visible features.

Conversely, if these discrepancies are numerous or fall outside this range of variability, the examination allows for the elimination of certain suspects, thereby redirecting the investigation. Finally, in the interest of impartiality, the specialist submits their comparisons to a second examiner, who conducts a new evaluation blindly, that is, without knowledge of the first examiner’s conclusions. This verification step is essential and serves as a guarantee of reliability. This methodology, recognized by the scientific community and referred to as ACE-V(Analysis-Comparison-Evaluation-Verification), helps to minimize the risk of error and bias to the greatest possible extent.

Superimposition (center) between a questioned earprint recovered at a crime scene (left) and the earprint of a suspected individual (right). The combined observations and comparisons between the incriminated earprint and the suspect’s left earprint strongly support the hypothesis that the questioned trace was produced by the suspect’s left ear rather than by another individual. Sébastien AGUILAR ©

Identification or earprint association?

Given current techniques, it is important to place this method in its proper context. The use of earprints in judicial investigations cannot lead to stricto sensu identification. However, depending on the intrinsic quality (ear morphology) and extrinsic quality (the condition of the surface, the lifting method, the powder used, the pressure applied, etc.) of the earprint, the specialist may establish a stronger or weaker degree of association. On average, and it must be emphasized that each case has its own specificities, the probability of a coincidental match is estimated at between one in one thousand and one in ten thousand.

Although an earprint alone cannot suffice to identify an individual, its analysis constitutes an investigative tool of undeniable value. Once a converging body of evidence is established, through investigative elements such as witness testimony, phone records, surveillance, or other forms of forensic evidence, an earprint becomes, in a sense, the screwdriver that tightens the link between different cases or between a case and a suspect.

Earprints and the justice system

In France, numerous cases involving the association of earprints have been handled, primarily by the courts of the Paris and Lyon metropolitan areas.

Publicly pronounced on February 17, 2016, by the Paris Court of Appeal (Division 4 – Chamber 10 of Criminal Appeals), ruling on an appeal against a judgment of the Créteil Regional Court (12th Chamber, October 16, 2016), the court addressed the use of earprints in a case of burglary with breaking and entering. The decision specifically stated that “a genetic profile was recovered at the location where forensic technicians had lifted a left earprint; it therefore follows from the combination of these two impressions that the defendant was indeed the source of both his DNA and the earprint, thereby validating the forensic earprint technique used by the police […] ; the comparisons between the various traces recovered at the crime scenes and the earprints taken from the defendant during police custody confirm that, notwithstanding his denials, his involvement in these five offenses is established.”

The judgment delivered on December 13, 2017, by the 14th Criminal Chamber of the Paris Regional Court, perfectly illustrates the combination of different types of evidence working together in the pursuit of truth. “Mr. X admitted to committing nineteen of the thirty-two offenses with which he was charged, describing the modus operandi systematically employed. His confessions were corroborated by investigators’ observations at each scene, by the results of comparisons conducted by forensic police between the earprints recovered and the defendant’s ears, and/or by the results of expert analysis carried out on the earprints. Furthermore, in certain offenses, these findings were reinforced by a match with the defendant’s DNA, a shoeprint consistent with footwear he was wearing, and the geolocation of his mobile phone in proximity to a burglary site. The thirteen burglaries or attempted burglaries with aggravating circumstances that were contested by the defendant were committed using a specific and strictly identical modus operandi to that of the admitted offenses. Earprints corresponding to those of Mr. X were recovered at six of the burglarized sites or attempted entries, including one residence where his DNA was also found on the front door. The seven other contested offenses occurred under similar temporal and spatial conditions, specifically, during the same timeframes and in the same buildings, even on the same floors. Moreover, Mr. X’s explanations appeared contradictory, as he told the investigating judge that he only operated in the 15th arrondissement, whereas he admitted to offenses committed in numerous other districts. The combination of these various elements carries sufficient probative value to establish guilt for all the charges brought.”

Conclusion

We are convinced of the potential of this type of trace evidence, and judicial practice in our courts demonstrates its utility. Earprints are an effective tool for judicial intelligence through the establishment of crime series, even before an individual is formally implicated. When compared against a suspect’s reference earprints, they provide a powerful associative indicator that judicial actors should not overlook. Naturally, absolute certainty should not be expected from this type of association. Nonetheless, the correlations established are sufficient to add a solid new string to the bow of forensic science.

Note

1. Establishment of a distinctive description of an individual, including the taking of photographic records (frontal, profile, and three-quarter left views).

Sébastien Aguilar: Chief Technician in Forensic Science at the Regional Directorate of the Paris Judicial Police, MSc in Criminal Sciences from the School of Criminal Sciences, University of Lausanne.

Christophe Champod: Full Professor of Forensic Science and Director of the School of Criminal Sciences, Faculty of Law, Criminal Justice and Public Administration, University of Lausanne.

Further reading

1. Sébastien AGUILAR, Benoit DE MAILLARD, Police Scientifique : Les experts au coeur de la scène de crime. Hachette, éd. 2017, pp. 119-125.

2. Christophe Champod, Ian W. Evett, Benoît Kuchler, « Earmark as evidence : a critical re- view », Journal of Forensic Sciences , Vol. 46, No 6, 2001, pp. 1275-1284

3. Stéphane Junod, Julien Pasquier, Christophe Champod, « The development of an auto- matic recognition system for earmark and earprint comparisons ». Forensic Science International, 2012, Vol. 222, Issues 1–3, pp.170-178

4. C. Van der Lugt, Earprint Identification. El- sevier Bedrijfsinformatie, Gravenhage, 2001, 318 p.

5. Joëlle Vuille, « Traces d’oreille et preuve à charge : le Tribunal fédéral n’est pas sourd aux droits de la défense ». Forumpoenale. Vol. 6, 2014, pp. 347-350.

6. Lynn Meijerman, Andrew Thean, George J. R. Maat, « Earprints in Forensic Investigations », Forensic Science, Medicine and Pathology, 2005, Vol. 1, Issue 4, pp. 247-256.

Article published in REVUE EXPERTS n°145 – August 2019

Tous droits réservés - © 2026 Forenseek