As in the Élodie Kulik case in 2011 and that of the “Prédateur des bois” in 2022, two casefiles reopened by the Cold Case Unit in Nanterre are now close to being solved thanks to familial DNA searching,

“They say you’re only betrayed by your own,” a proverb that takes on its full meaning here. Two murders committed twelve years apart and seemingly unrelated have now been traced back to one and the same suspect—thanks to a genetic link established between members of the same family.

In 1988, fifteen-year-old Valérie Boyer was found with her throat slit along the railway tracks in Saint-Quentin-Fallavier. In 2000, forty-year-old Laïla Afif was shot dead in the head in La Verpillière. The only common factor between the two crimes was geographical proximity, as both occurred in neighboring towns in the Isère department. Lacking solid leads or similarities in the modus operandi, the investigations soon came to a standstill—until March 2024. More than twenty years later, the Cold Case Unit, created in 2022, reopened the Laïla Afif case and ordered new DNA analyses on samples recovered from the crime scene.

Proof through familial DNA

These forensic analyses, extended through the use of familial DNA searching, led investigators to identify, within the National Automated DNA Database (Fichier National Automatisé des Empreintes Génétiques – FNAEG), an individual previously implicated in another case whose DNA showed a 50% genetic match with the profile obtained in the Afif case. And as the immutable laws of genetics dictate—each person shares half of their genome with their biological parents and children—the investigators logically traced the lead back to the man’s father. Betrayed by his son’s DNA, Mohammed C. has now been indicted not only for the murder of Laïla Afif, but also for that of Valérie Boyer, as the reopened investigation revealed striking connections between the two crimes. The latter case is part of the notorious “Disparus de l’Isère” (the Isère disappearances) series, a string of disappearances that made national headlines in the 1980s and is already under review by the Cold Case Unit.

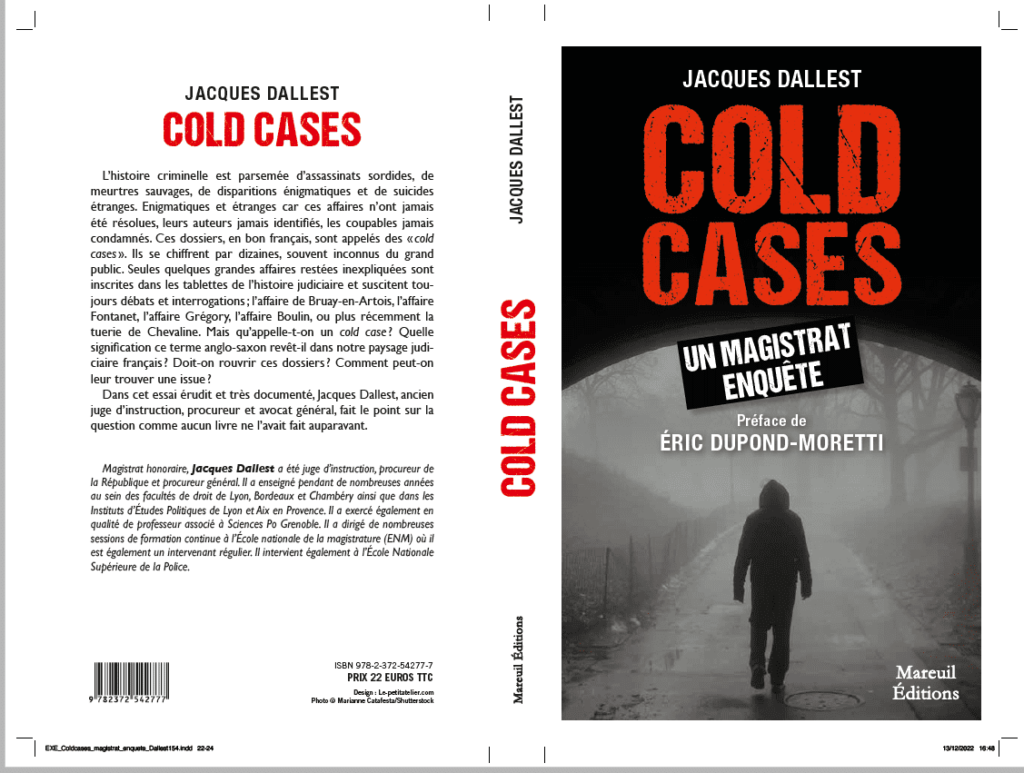

Further reading: COLD CASES UN MAGISTRAT ENQUÊTE (Cold Cases – A Magistrate Investigates), by Jacques Dallest

Criminal history is marked by sordid murders, brutal killings, mysterious disappearances, and puzzling suicides. Mysterious and puzzling because these cases have never been solved—the perpetrators never identified, the culprits never convicted. In proper French, these cases are referred to as “cold cases.” They number in the dozens and are often unknown to the general public. Only a few major unsolved cases have found their place in the annals of judicial history and continue to fuel debate and speculation: the Bruay-en-Artois case, the Fontanet case, the Grégory case, the Boulin case, and, more recently, the Chevaline shootings. But what exactly is a cold case? What does this English term signify within the context of the French judicial system? Should these cases be reopened? And after so many years, how can justice still be served? In this scholarly and meticulously documented essay, Jacques Dallest—former investigating judge, public prosecutor, and Advocate General—offers a comprehensive analysis of the issue as no book has ever done before.

Order online.

Tous droits réservés - © 2026 Forenseek