The olfactory trace can be defined as the identification of an individual by their scent. Just like fingerprints, genetic profiles, and now digital footprints, the olfactory trace could, over time, be used as a specific marker of an individual.

The olfactory trace originates from the odor emitted by a human being, which may either be left on a surface following contact, or remain suspended and carried in the air after the person has passed by. Although the notion of an odor trace is not new, it was not until the end of the 20th century that the feasibility and relevance of collecting such traces—initially not obvious (unlike a bloodstain, a flammable liquid spill, or a ballistic impact, which are “visible”)—were demonstrated. Advances in collection materials (polymers, fabrics, etc.) also made it possible to collect and preserve these traces. At the same time, analytical developments (notably chromatography) made it possible to better detect these traces and to gain a more accurate understanding of their composition.

It is now possible to collect such traces at a crime scene, as well as directly from individuals themselves, for comparison purposes. The so-called “odorology” or “forensic scent identification” techniques using dogs are based on this comparison between an odor collected at a scene (odor trace) and a bodily odor taken directly from an individual (direct odor).

Odor is a complex combination of several hundred molecules. Among them, one can distinguish a so-called primary component, consisting of a genetically determined static part that is thought to remain stable in an individual over time. Added to this are more variable components: a secondary odor, influenced by parameters such as physical or psychological activity, diet, and environment; and a tertiary odor, derived from cosmetics and other exogenous compounds in general.

Despite this complexity, the effectiveness of dogs in locating missing persons or following tracks is well established. However, this approach will always face limitations in the formal identification of an individual who is no longer present at a given location and time. These limitations are due, so far, to the lack of knowledge about how the canine sense of smell works, and particularly about which molecules are involved in recognizing an individual—an aspect that remains a mystery, even in the scientific literature.

The lack of information about the trace itself and about the odor discrimination process carried out by dogs during tracking is a real obstacle and diminishes the evidential strength of the method.

Moreover, the potential bias introduced by the line-up procedure itself, as well as the question of how to interpret a dog’s failure to mark (absence of trace or failure of detection), also arise.

These observations have led specialists at the IRCGN to consider, alongside canine methods, alternative approaches involving collection techniques, chemical analyses, and statistical processing, in order to exploit this promising trace by other means.

With a view to formal identification in criminal proceedings, the use of two orthogonal techniques (canine teams and laboratory analyses) that ultimately converge on the same individual would considerably strengthen the evidential value of the trace.

In the long run, a “laboratory-based” approach would thus provide genuine support for dog-based identifications. Indeed, a dog’s marking could be confirmed in the laboratory, and in cases where no marking occurs due to a partial or degraded trace, laboratory classification could still help guide investigators and magistrates in their inquiries.

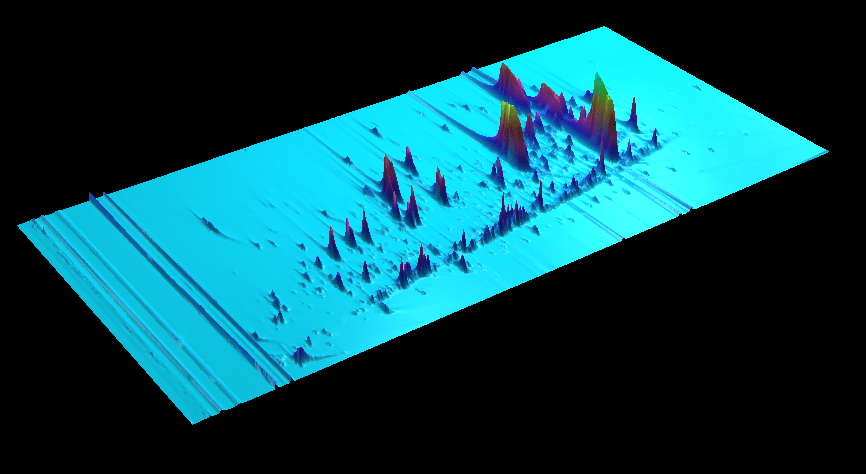

The “Olfactory Trace” project, led by the IRCGN, is built on an evolutionary design principle. It simultaneously involves work on sample collection—through the development of methods and tools that can be easily used in the field (including a patented sampling pump)—the use of advanced analytical tools such as comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry, as well as data processing techniques (computational and statistical). The IRCGN’s aim is to provide investigators with a solution to classify, and even individualize, in order to increase the evidential value of the information provided by the dog.

This research project may also address issues beyond the forensic field, since it involves the identification of chemical molecules secreted by the human body, some of which are of interest to the medical community, particularly for diagnostic purposes.

For example, the “KDog COV ” project, led by the Institut Curie, is a human-based study aimed at analyzing human odor to detect potential chemical markers of breast cancer using analytical chemistry techniques. The objective of this research program is to develop a simple, low-cost, and non-invasive screening method for breast cancer. Analyses are carried out in partnership with the IRCGN, which has already developed methods for sampling and analyzing human odor in the forensic field.

Reference of this work:

- [1] V. Cuzuel, G. Cognon, I. Rivals, C. Sauleau, F. Heulard, D. Thiébaut, J. Vial, Origin, analytical characterization and use of human odor in forensics, J. Forensic Sci. 62 (2017) 330–350. doi:10.1111/1556-4029.13394.

- [2] V. Cuzuel, E. Portas, G. Cognon, I. Rivals, F. Heulard, D. Thiébaut, J. Vial, Sampling method development and optimization in view of human hand odor analysis by thermal desorption coupled with gas chromatography and mass spectrometry., Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 409 (2017) 5113–5124. doi:10.1007/s00216-017-0458-8.

- [3] V. Cuzuel, A. Sizun, G. Cognon, I. Rivals, F. Heulard, D. Thiébaut, J. Vial, Human odor and forensics. Optimization of a comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography method based on orthogonality: How not to choose between criteria, J. Chromatogr. A. 1536 (2017) 58–66. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2017.08.060.

- [4] V. Cuzuel, G. Cognon, D. Thiebaut, I. Rivals, E. Portas, A. Sizun, F. Heulard, Reconnaître un Suspect grâce à son Odeur : du Chien aux Outils Analytiques, Spectra Analyse, 318 (2017) 38–43.

- [5] V. Cuzuel, R. Leconte, G. Cognon, D. Thiébaut, J. Vial, C. Sauleau, I. Rivals, Human odor and forensics: Towards Bayesian suspect identification using GC × GC–MS characterization of hand odor, J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 1092 (2018) 379–385. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2018.06.018.

- [6] I. Rivals, C. Sautier, G. Cognon, V. Cuzuel, Evaluation of distance‐based approaches for forensic comparison: Application to hand odor evidence, J. Forensic Sci. (2021) 1556-4029.14818. doi:10.1111/1556-4029.14818.

- [7] M. Leemans, I. Fromantin, P. Bauër, V. Cuzuel, E. Audureau, Volatile organic compounds analysis as a potential novel screening tool for breast cancer: a systematic review (submitted)

Tous droits réservés - © 2026 Forenseek