Lieutenant Colonel Pham-Hoai served as head of the biology department at the Criminal Research Institute of the French Gendarmerie (IRCGN) and as a DNA expert at the Court of Appeal of Versailles. Among his most emblematic cases as an expert, he conducted with his former team the genetic analyses related to the violence surrounding the death of Adama Traoré in 2016, and the examination of Nordahl Lelandais’ vehicle in connection with the abduction and murder of Maëlys de Araujo in 2017. Before becoming an expert, he gained recognition for his original contribution to solving the murder of Élodie Kulik. Lieutenant Colonel Pham-Hoai reflects on this initiative, in which familial DNA searching led to the resolution of this long-running investigation.

The context of a criminal case

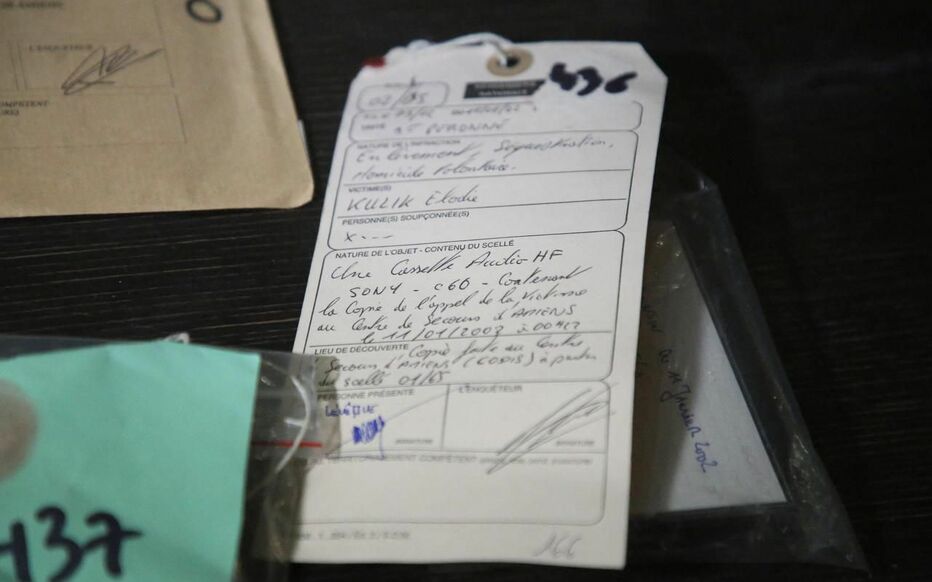

On the night of January 10–11, 2002, Élodie Kulik, 24 years old, was involved in a road accident near Péronne (Somme). Just before her ordeal, the victim managed to call emergency services. On the audio recording, two male voices can be heard. Élodie Kulik was then raped and killed at a green-waste landfill near the accident site. Her attackers set fire to the upper part of her body. The semi-charred remains were discovered on the morning of January 12, 2002, by a local farmer. The Gendarmerie was assigned the case and began its forensic investigation. A male DNA profile was identified both on the victim’s body and on an object found nearby. This same profile was entered into the national automated DNA database (FNAEG). No match was found for the DNA trace recovered from the crime scene. At the time, in 2002, the database was still in its early stages, with few profiles recorded. Investigators from the Amiens Research Section then launched extensive DNA collection operations from all men of potential interest to the case. Convicted sex offenders not yet in the database, as well as individuals named by anonymous tips or public rumors, were sampled—without success.

In July and August 2002, two more young women, Patricia Leclercq and Christelle Dubuisson, were murdered in the Picardy region. It was established that Patricia Leclercq had been raped before being killed. For these two murders, a different male DNA profile was obtained—again without a match in the FNAEG. This new genetic evidence reinforced the idea that at least two serial killers were operating in Picardy targeting young women. The media frenzy intensified, and public emotion reached a peak in the region. In September 2002, Nicolas Sarkozy, then Minister of the Interior, met with the families of the three victims to express his support. Additional resources were allocated, and the investigators continued collecting DNA samples from all suspects. Through this process, they identified Jean-Paul Leconte as the murderer of Patricia Leclercq and Christelle Dubuisson. However, it was established that Leconte was incarcerated in January 2002 and had not been granted leave. He was therefore ruled out as a suspect in the rape and murder of Élodie Kulik.

Despite the media storm and these unfortunate coincidences, the real challenge for investigators remained above all a human one. The Kulik family had already endured devastating losses. Her parents had lost two children in a car accident in the mid-1970s. Despite this tragedy, the couple had chosen to rebuild their family a few years later, giving birth to Élodie and her brother Fabien. Élodie’s murder became the final blow for her mother, who attempted suicide. Her act led to a vegetative coma that lasted nine years before her death in 2011. Jacky Kulik, Élodie’s father, turned his despair into determination to ensure that his daughter’s murder would be solved. He mobilized support, engaged with the media, and organized white marches to prevent the case from being forgotten. He even offered a reward to anyone who could provide information leading to the arrest of the perpetrators.

Front page of Courrier Picard — Ambush on the departmental road. Credit: France 3 Nord–Pas-de-Calais

Investigators persevered in their efforts, collecting DNA samples from over 5,000 individuals by 2010. None of them matched the DNA profile found at the scene. At the same time, no lead made it possible to identify the second suspect heard on the audio recording, in the absence of his genetic profile. Several investigators and investigating judges succeeded one another on the case. The investigation had reached a dead end.

So how could a young gendarmerie captain, with a scientific background and just beginning his career in judicial police, help?

A Fresh Look at the Élodie Kulik Case file

Assigned to the criminal investigation division in 2009, I arrived with two master’s degrees—one in health engineering and the other in molecular biology. My first three years of service were spent at the Criminal Research Institute of the National Gendarmerie (IRCGN), where I was part of the interministerial committee in charge of the national DNA database (FNAEG). Suffice it to say, I knew little about criminal investigations beyond what I had been taught at the National Gendarmerie Officers’ School. My superior at the time, Colonel Robert Bouche, put me in charge of the property crime division and gave me the additional mission of learning how to lead investigations. Simple at first but quickly grew more complex, like solving an equation. I was clearly not the Institution’s new Sherlock Holmes, but I quickly understood that a well-conducted investigation is nothing more—and nothing less—than a scientific demonstration. The parallel is striking: hypotheses are formed (I suspect Pierre and Paul may be involved in the crime), tested through experiments that generate data (witness statements, physical and technical surveillance provide those data), and the results are interpreted (if my witness testimony and technical surveillance show that Pierre and Paul were indeed present at the crime scene at the time of the offense, can I for all that assert that they are the perpetrators?). By applying scientific reasoning and rigor, I was able to bring objectivity and avoid any form of arbitrariness. This clinical approach to examining the elements of an investigation—regardless of the outcome— allows one to get as close as possible to the factual reality. The hardest part is maintaining some distance from promising early leads that may turn out to be wrong. A good investigator is, in a sense, a scientist without knowing it.

In August 2010, the commander of the Research Section decided to promote me to head of the Crimes Against Persons Division, which handles homicides and narcotics trafficking. That was when I discovered the Kulik case in detail and its scope. Having never taken an interest in this murder before my assignment to Amiens, I read the investigative reports with a fresh perspective, just as Colonel Bouche intended. Scientific reasoning immediately took precedence over any other considerations. First and foremost, I carried out my own work of gathering and synthesizing the data from the case file, avoiding any shortcuts or assumptions.

Judicial evidence seal containing the audio cassette of Élodie Kulik’s call to the Amiens emergency center on January 11, 2003. Credit: Courrier Picard – Frédéric Douchet

As I read through the investigative reports, I realize that all suspects—both the most relevant and the less likely—had been sampled. As soon as a man became a suspect for probable and/or plausible reasons, his genetic profile was obtained and compared with that of the crime scene trace. By 2010, over 5,000 individuals had been tested—the equivalent of a medium-sized town.

All potentially suspicious men, whether they lived or had lived near the crime scene, or were designated through public rumor (in other words, persistent gossip), had their DNA sampled, all without success. What does this teach me about the suspect being sought, and more specifically, about his absence from the DNA sampling operations?

Three explanations could account for his absence:

- He had never been involved with the justice system before or after the rape.

- He fled to a place where he could never be located and sampled.

- He has died since the murder.

Another factor must be taken into account: the extensive media coverage of the case. The press repeatedly made public the fact that a male DNA profile had been recovered at the crime scene. If the suspect is still alive, there is no doubt that he is aware of this information. This gave him a definite advantage—a head start—allowing him to remain on guard. However, this advantage could be compromised by the second suspect, who could at any time denounce him to save himself. Yet since 2002, that has not happened. It seems reasonable to assume that if the second suspect has never come forward, he will continue to stay silent—especially if he is convinced that his own DNA was not found at the crime scene.

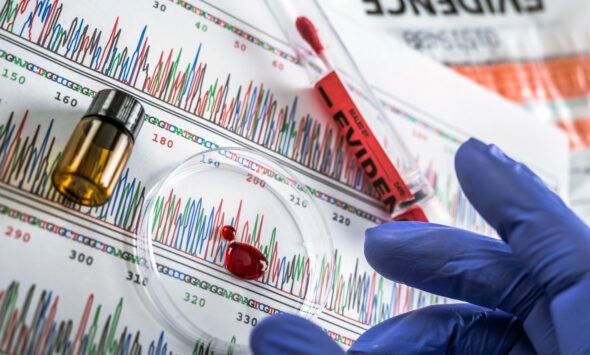

In 2010, a conclusion becomes clear to me: the most promising element for identifying the two suspects is the DNA profile left by one of them at the scene. Nevertheless, how can one identify an individual based solely on his genetic profile if it is not in the database—and likely never will be? How can we obtain a last name that could revive the investigation? This is where genetic knowledge, combined with the capabilities of the FNAEG, comes into play.

Storage of biological evidence at the Central Service for the Preservation of Biological Samples (SCPPB), attached to the Institut de Recherche Criminelle de la Gendarmerie Nationale (IRCGN). Credit: PGJN

Familial DNA searching: a new use of genetics in criminal investigation

The DNA profiles recorded in the FNAEG are composed of markers: in 2002, there were 15 of them, with a potential increase to 17. This does not include the marker determining sex. Each marker carries two alleles: one inherited from the father, the other from the mother. Thus, the genetic profile of an individual, defined by 15 markers, contains 30 alleles. Of these 30 alleles, half are identical to those of the individual’s father, and the other half to those of the mother.

When comparing a trace to the genetic profile of an individual, the FNAEG’s comparison engine searches for strict allele matches. In other words, in the case of a 15-marker individual, all 30 alleles must be identical to those of the trace for the database to return a hit (commonly referred to by experts as a “match”) to the investigator. If not, the search is deemed unsuccessful. Yet there are cases where partial correspondences may be of value: those in which the parent of a trace donor is sought.

Indeed, if the suspect is not in the database, perhaps their parents or children are. These relatives could lead investigators to the suspect by providing a surname. From there, the suspect’s family tree can be reconstructed using civil registry records. The method is straightforward: if the suspect’s parent is in the database, the search engine should return all individuals whose profiles share 50% of their alleles with the crime scene trace. Complementary analyses such as paternity or maternity tests can then definitively confirm the kinship link between the individual and the trace.

As this idea seemed coherent, I began researching whether it had already been implemented abroad. Following a scientific approach, I conducted a literature review. I humbly assumed that other scientists abroad must have had the same idea, implemented it, and published their findings. Their experience—whether successful or not—could help me save time. This search led me to a case report published in the renowned journal Science. The article described the case of the “Grim Sleeper,” a serial killer responsible for at least eleven murders of young women in California between 1985 and 2010. Although he had left his DNA at multiple crime scenes, he had always eluded law enforcement and was never entered into the database. North American experts used the same approach I had imagined and successfully identified his son whose genetic profile was registered for prior offenses. The article also mentioned other U.S. states using this technique. At this stage of my research, I was convinced that the FNAEG must already be using such searches, albeit on an exceptional basis. To my great surprise, when I contacted the database representatives, I learned that this scenario was not provided for.

The publication of familial DNA searching in a major scientific journal reassured me of the validity of my approach. Thanks to contacts from my previous posting, I submitted my proposal to the Directorate of Criminal Affairs and Pardons at the Ministry of Justice. Their response confirmed that it would be a first in France: the FNAEG had never been envisaged in this way. Nothing prohibited such a search, but nothing explicitly allowed it either. The immediate question was whether the technique would be legally valid if it led to the identification of one of Élodie Kulik’s attackers. A year of debate followed to ensure that the investigation would not be compromised by this new method. The decision finally came in 2011: we were authorized to use the technique. If successful, it would not constitute grounds for procedural nullity. In the background, it was even envisaged that the method could be extended to a broader range of cases.

Once authorized, the request was submitted to search the FNAEG for all individuals sharing half their alleles with the crime scene trace. As with our North American counterparts, the gamble paid off and yielded a second surprise—this time a fortunate one: the suspect’s father was in the database. A paternity test based on comparing the Y chromosome in the trace and that of the identified individual confirmed that they belonged to the same paternal line. With the surname now identified, we reconstructed the suspect’s family tree. We traced it back to his eldest son, the likely source of the trace. Then came a third, less pleasant surprise: the suspect had died in 2003 in a road accident, just one year after the crime. After ensuring that no other family member could be involved, his body was exhumed in early 2012. The analysis confirmed that his genetic profile matched the crime scene trace.

The suspect’s death shortly after the events explained his absence during DNA collection operations from 2002 to 2010. The experiments permitted to validate the hypotheses. Even if difficulties lay ahead, I knew that the case would eventually be solved. Once investigators have a lead—and even more so a name—they pursue it to the end. Extensive work was carried out to reconstruct the suspect’s family and social environment prior to his death. That’s how, by mid-2012, the second suspect was identified. He was later confirmed by voice recognition from the emergency call made by Élodie Kulik on the night of her death. Tried at first instance in December 2019 and again on appeal in July 2021, he was sentenced to 30 years in prison for the rape and murder of Élodie Kulik.

When people ask how I came up with the idea of searching for a relative of the suspect in the FNAEG—an idea some consider brilliant, though it is in fact very simple—I always give the same answer: there’s nothing extraordinary in what I did. It was scientific reasoning combined with investigative experience. Hypotheses were formulated, then tested using investigative tools. Results were considered with appropriate distance. Discussions were held with more experienced gendarmes—because collective reflection is always better than facing a difficult result alone. This is something any scientist or any individual with intellectual rigor and logic could do.

Tous droits réservés - © 2025 Forenseek