From as far back as crime has existed, the offender’s natural reflex has been to conceal their traces in an attempt to escape justice. That said, to succeed, the traces of their action or passage must first be visible to the naked eye…

“No one can act with the intensity implied by criminal behaviour without leaving multiple marks of their passage. Sometimes the offender has left at the scene the marks of their activity; sometimes, by the opposite action, they have carried on their person or on their clothing the evidence of their presence or of their act.”

— Edmond LOCARD, L’enquête criminelle et les méthodes scientifiques, Flammarion, Paris, 1920.

Microtraces: a very discreet clue

As Edmond LOCARD explained in his treatise on criminalistics, the perpetrator leaves traces of themselves and of their environment on the victim and at the crime scene and, conversely, takes away traces of their action. A criminal investigation therefore relies in part on the material traces found at the site of an offence or on a crime scene. To that end, investigators and forensic scientists methodologically gather traces and clues.

Over the past two decades, television series have broadly popularized the importance of collecting traces at a crime scene or from a suspect. The possibilities for exploiting those traces to solve an investigation are now well known to the general public. Television and the internet have doubtless also contributed to educating future offenders by informing them about the types of traces that can incriminate them.

Yet one type of trace remains relatively confidential today: the infinitesimally small. This world, where the human eye reaches its limits, is also populated by exploitable traces known as “microtraces.” Their dimensions are generally smaller than a millimetre and escape our perception. The only challenge is to be able to collect them without seeing them — by means of systematic sampling — in order to exploit them later.

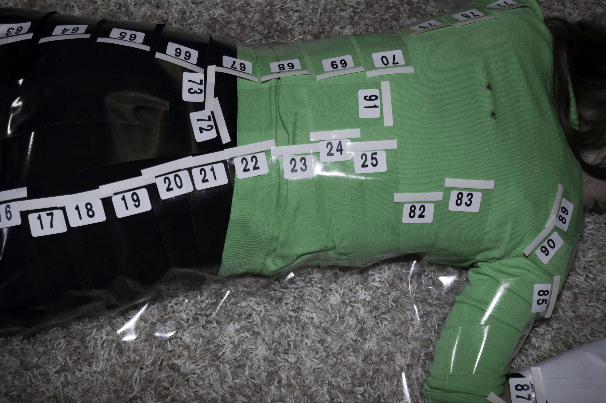

Systematic sampling of microtraces (notably fibres and hairs) using the 1:1 taping technique (application of pre-numbered adhesive strips) on a victim’s body. Sampling avoids the area around ballistic orifices so as not to compromise analysis and the estimation of firing distance. This photograph comes from a reconstruction for instructional purposes, with the voluntary participation of an actress in the role of the victim. © 2014 INCC DJT King’s Group.

Microtraces of biological origin

A single cell from the human body contains all the material necessary to establish our genetic profile — in other words, our DNA. It is therefore not necessary for an offender to wound and bleed — or to deposit other biological fluids (notably saliva or semen) — to leave their DNA at a crime scene. Indeed, any contact with the victim or manipulation of objects in the victim’s environment can transfer a few skin cells and potentially allow recovery of that individual’s DNA. In the absence of direct contact, microscopic projections of saliva or blood can also lead to DNA identification.

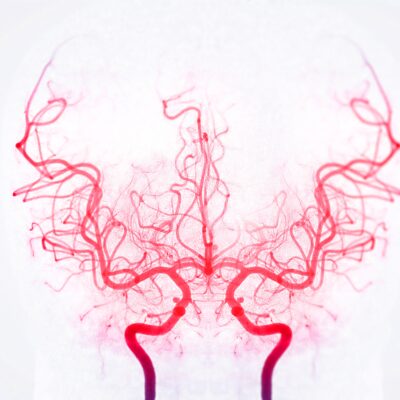

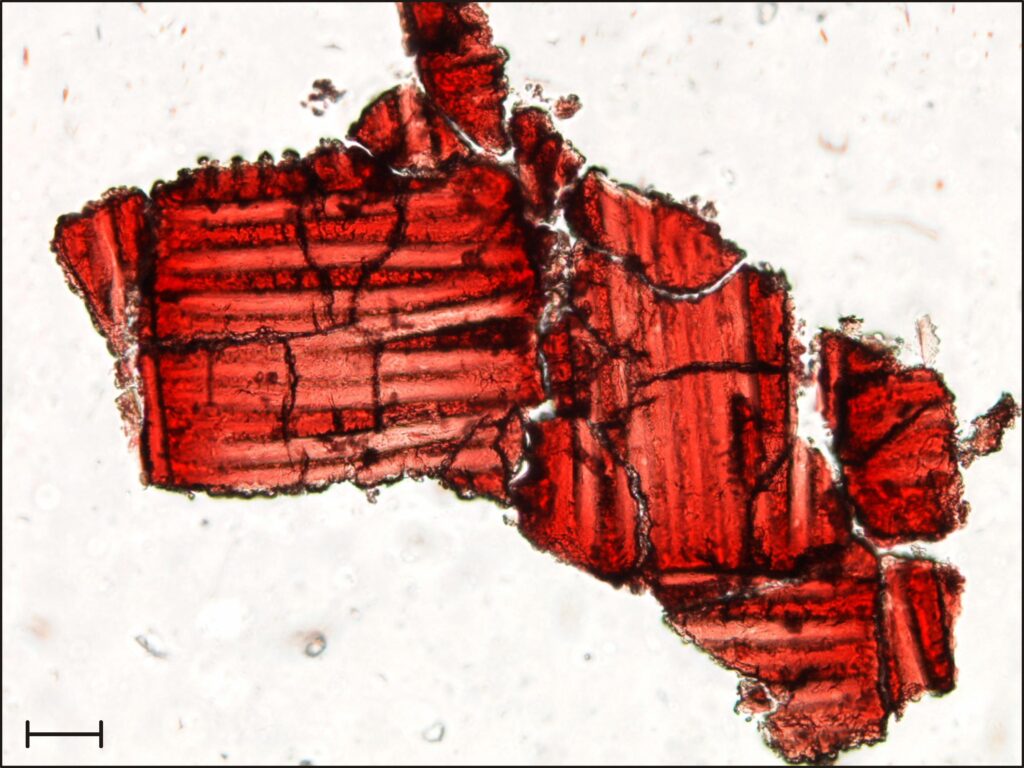

Microscopic image (200× magnification, with the metric scale representing 50 microns) of a dried blood microparticle. This particle measures approximately 600 microns in length and 300 microns in width, corresponding to an area of less than one-fifth of a square millimetre. Blood microparticles originate from tiny projections of blood, undetectable to the naked eye, particularly on the black (or very dark) clothing of an offender. Systematic adhesive tape-lift sampling on clothing will clearly reveal such microtraces of blood. Depending on their dimensions and the quality of the genetic material, these microparticles may, for example, lead to recovery of the victim’s DNA. The illustrated microparticle shows horizontal and vertical striations, indicating that the blood dried on the fabric of the garment in question. © 2014 Elsevier – Forensic Science International 246 (2015) 50–54.

A clump of hair torn from the victim’s hand is no longer the type of evidence an offender will likely leave behind. However, a victim’s clothing—or, in the case of sexual assault, their undergarments—may retain microscopic hairs or hair fragments, also capable of leading to the offender’s DNA.

When crimes occur outdoors, nature can also aid justice through microscopic debris of minerals or plants. Such traces may be recovered, for example, from the soles of shoes, clothing, or even the pockets of an offender. These microtraces may indicate the nature of the soil or vegetation at the crime scene, or the location where the victim may have been moved after the incident.

Without being exhaustive, another type of biological microtrace—diatoms—may be found in a victim’s lungs and assist in determining whether the victim drowned in the waters where they were discovered (accidental hypothesis) or whether the scene was staged, for instance, with prior drowning in a water supply system. Diatoms, a type of unicellular microalgae, may also differ between the waters at the discovery site and the waters where the drowning actually occurred, thereby redirecting the investigation to the original crime scene.

Microtraces of chemical origin

Firearms are frequently used or displayed in criminal acts. Handling or discharging a firearm contaminates the offender’s hands, face, and clothing with gunshot residues. These residues are microscopic particles with distinctive morphology and chemical composition, although the latter can vary depending on the ammunition and weapon involved. Clothing is also particularly useful for revealing criminal contacts. Indeed, friction between two textiles in contact leads to the transfer of microscopic entities: textile fibres. These fibres, the basic components used to produce textile threads and, ultimately, garments, are also present on the surface of clothing, where they may be exchanged through friction. Such transfers can be even more pronounced when the interaction between victim and offender is violent. A victim’s clothing therefore harbours textile fibre microtraces originating from the offender’s garments, particularly in areas of concentrated contact, such as the neck in a case of strangulation. In line with the principles established by Edmond LOCARD, the offender will also carry away microtraces of fibres originating from the victim’s clothing.

Illustration of the presence of fluorescent green textile fibres deposited by rubbing a fluorescent green fabric against the surface of a black fleece garment. For instructional purposes, the green fabric used consists of long, thick fibres showing intense green fluorescence. In real criminal cases, however, fibre microtraces are generally shorter and finer, and they exhibit no spontaneous fluorescence. They are therefore practically invisible to the naked eye and must be detected on systematic samples (via adhesive tape-lifts) using microscopes. © INCC – Lisa Van Damme

A hit-and-run accident can often have serious consequences for the injured victim, particularly when the victim is a vulnerable road user such as a pedestrian or cyclist. In the absence of video surveillance and automotive debris at the accident site, microscopic traces of automotive paint may be recovered from the victim’s clothing. Their analysis can lead to the identification of a make—or even a model—of vehicle to be traced by the police. Once a suspect vehicle has been located, a formal comparison may be made with the paint from the damaged areas. In most cases, such comparison remains possible even if the vehicle has been repaired in the meantime.

Microtraces: a broad subject

Microtraces are as diverse and varied as the biological or chemical materials capable of dispersing or fragmenting into microscopic evidence. The aim of this article is not to be exhaustive; the examples mentioned here briefly illustrate the most common microtraces encountered in criminal investigations. Each type of microtrace requires specific collection methods by trained personnel and specialized analytical techniques in forensic laboratories—too detailed to be explained in this general overview. More targeted articles will be better suited to detail the forensic value of each type of microtrace in criminal investigation.

Tous droits réservés - © 2026 Forenseek