The recurring question in many criminal investigations is undoubtedly the following: what really happened? This seemingly simple question is often difficult to answer, even though both the tactical and scientific aspects of modern criminal investigations benefit from cutting-edge technologies. Added to this complexity are cases in which the victim is deceased, the suspect provides incomplete statements, or several suspects or witnesses offer contradictory versions of events. Investigators then have no choice but to turn to traces and physical evidence that may shed light on the modus operandi of the crime.

Activity as a key concept

The unfolding of a criminal act often involves an intense level of activity that sharply contrasts with the routine activities of daily life. Taking, for instance, a case of manual strangulation, the criminal act is likely to involve an initial struggle, followed by strangulation leading to death, and possibly the movement of the body in an attempt to conceal the crime. Such activity inevitably generates multiple points of contact between victim and perpetrator, resulting in the transfer of traces, as described by Edmond Locard in his Treatise on Criminalistics.

Verifying the presence or absence of traces is the first essential step in any criminal investigation. This preliminary search can already provide valuable clues to suggest a criminal act or the suspect’s presence at the scene. However, not all traces are immediately visible—examples include touch DNA or microtraces. Relevant sampling can later yield additional information through laboratory analyses. It should nevertheless be remembered that the absence of traces does not necessarily indicate an absence of contact, and conversely, the presence of traces may sometimes be legitimate.

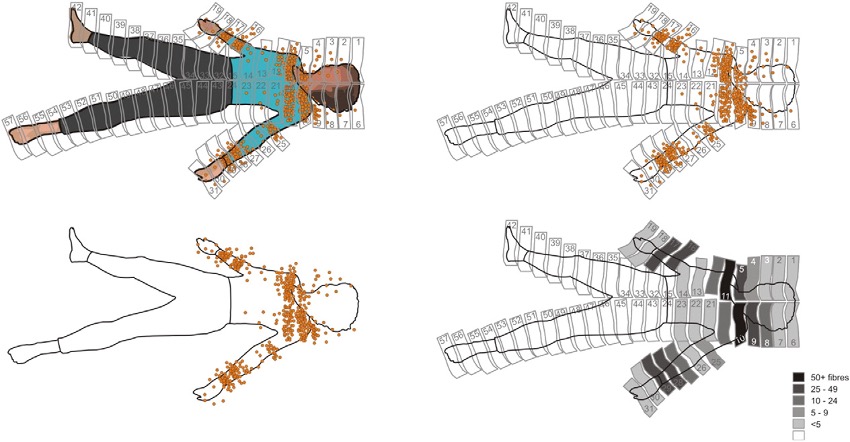

Attempting to understand the modus operandi of a crime requires examining traces not merely in terms of their presence or absence, but rather in relation to their quantity and/or distribution. In the case of textile fibers, forensic literature has shown that intense and/or repeated contact—as occurs during a criminal act—results in the transfer of a greater number of fibers than ordinary, legitimate contact in daily life. As for the location of these fibers, it is often linked to the area where the most intense activity occurred, such as the neck region in cases of manual strangulation. The level of activity during the criminal event can therefore be inferred from both the quantity and distribution of transferred textile fibers.

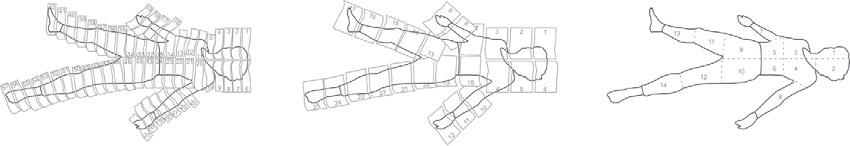

Different ways of representing the distribution of fiber traces on the victim’s body, used to illustrate the fiber examination report and facilitate understanding of contact areas. The colored image (top left) represents the actual crime scene photograph. The three other images show a schematic version of the body derived from that photograph. The position and density of the fiber traces can be represented using small colored symbols (here, orange dots) or by coloring the adhesive tape areas according to a graded color scale. © 2015 The Chartered Society of Forensic Sciences. Published by Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved

The absence of traces does not always indicate the absence of contact, and the presence of traces may also have a legitimate origin.

Microscopic textile fiber traces

Textile fibers—microscopic entities and the fundamental components of textile materials—are generally present as protruding elements on the surface of clothing, from which they can be transferred through contact. The exchange of microscopic fiber traces between victim and perpetrator typically occurs through friction between their garments, particularly in areas of intense or repeated contact. It should be noted that fibers can also be transferred onto other substrates such as skin or hair. The exchanged fiber traces thus serve as microscopic evidence that contact has taken place—they simply await to be uncovered!

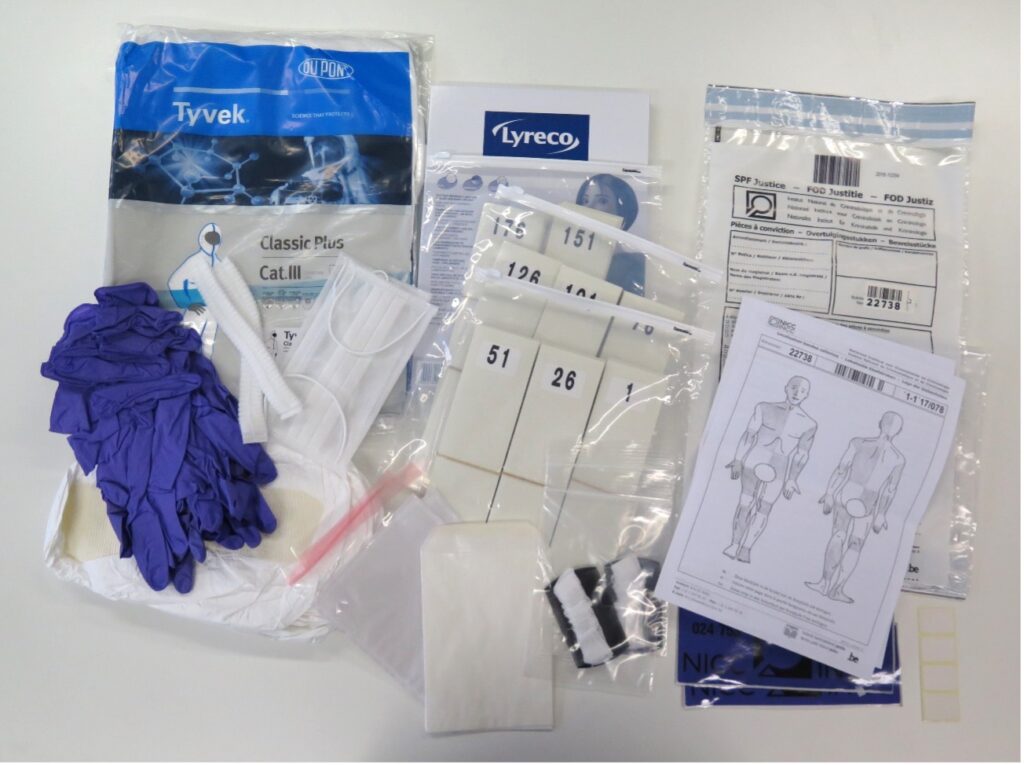

Microscopic textile fiber traces are usually invisible to the naked eye and therefore require systematic sampling. The most widely used collection method in Europe is the application of adhesive tapes over the entire surface likely to bear traces—a technique known as taping or tape-lifting. The manner in which adhesive tapes are applied depends on the working conditions and the objective of the collection. A “zonal” application (each adhesive tape is dabbed multiple times to cover an area larger than its own dimensions) may be considered sufficient when the objective is to preserve traces quickly, or when the garment has already been heavily handled—for instance, by emergency personnel. Conversely, if precise localization of traces is required, the ideal method is the “1:1” technique (each adhesive tape is applied once only to cover an area equivalent to its own size, with adjacent tapes placed edge to edge to cover a wider surface). The more precise the sampling technique, the clearer both the localization and quantity of fiber traces will appear on the trace mapping diagram produced after laboratory processing. It is worth noting that the “1:1” technique is recommended when blood or touch DNA traces are also to be analyzed on the clothing, as the “zonal” technique may disperse or dilute biological material.

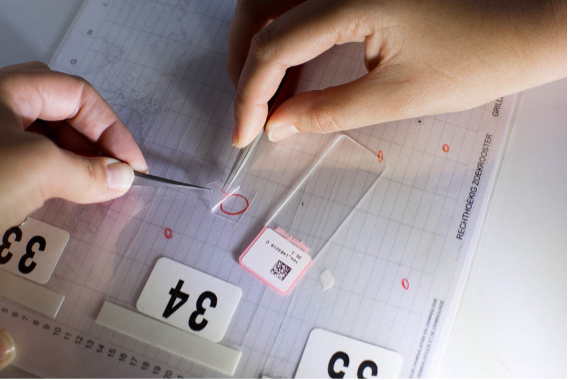

The search for microscopic fiber traces on adhesive tapes is still carried out entirely manually. In the absence of automated equipment, the laboratory analyst examines each adhesive strip under a stereomicroscope, looking for relevant traces. For instance, if the suspect was wearing a red cotton T-shirt, the analyst examining the victim’s samples will focus attention on red cotton fibers of a similar hue to that of the suspect’s garment. The detected traces are usually marked directly on the adhesive tape with an indelible marker, allowing for easy localization and counting.

The next step involves analyzing part or all of the recovered traces, after carefully extracting them from the adhesive tape and mounting them individually on properly labeled glass slides to ensure full traceability. According to forensic literature, optimal discrimination is achieved by combining high-magnification microscopic examination (typically 400×) with objective color measurement obtained through microspectrophotometric absorbance analysis. The chemical composition of synthetic fibers may also be verified, when necessary, using infrared spectroscopy. Fiber traces exhibiting the same properties as those of the comparison garment are described as matching or indistinguishable from an analytical standpoint.

In cases where there is no prior information regarding the clothing worn by the perpetrator, the same type of analytical work can still be conducted, but in a more investigative approach.

Knowing both the quantity and location of the so-called corresponding traces makes it possible to establish a trace map on the victim’s body—provided that sampling covered the entire body (clothing, skin, and hair) of the deceased. A simpler trace diagram can also be produced when at least the victim’s clothing has been promptly collected following seizure.

In the absence of information regarding the clothing worn by the perpetrator, a similar analytical approach can still be undertaken, albeit in a more investigative manner. In this case, the laboratory analyst must identify, on the adhesive tapes, fibers of similar appearance (shape and color) that recur consistently and are foreign to the victim’s clothing. The marked traces are then analyzed to determine whether they indeed form a group of fibers indistinguishable from one another from an analytical standpoint. If confirmed, the properties of this fiber group—particularly color and chemical composition—may be communicated to investigators to help target suspect garments during future searches. Such garments can subsequently be used as comparison material for the fiber traces, or analyzed for other types of forensic evidence such as blood or touch DNA.

The search for microscopic textile fibers is presented here primarily from the perspective of criminal contact between a victim and a murderer, involving the systematic collection of microtraces from the victim’s body at the crime scene. This procedure follows a standardized forensic protocol, notably applied in Belgium. However, the sampling and examination of fiber microtraces can, of course, be performed on other substrates besides the body or clothing of the victim—such as a suspect’s garments, vehicle seats or trunk, a knife, or any other object used as a weapon.

The forensic examination of textile fibers remains a largely overlooked discipline, the value of which is often underestimated.

Figure 2: Microtrace collection technique using adhesive tapes applied to a victim’s body. The “1:1” technique is illustrated (left) with small adhesive strips that conform to the body’s morphology, and (center) with wider adhesive strips allowing for faster collection (“semi-1:1”). The “zonal” technique is illustrated (right), showing a schematic division of the body into multiple areas that are successively dabbed with adhesive tapes. © 2015 The Chartered Society of Forensic Sciences. Published by Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved.

The crucial role of the fiber expert

The forensic examination of textile fibers is a little-known discipline, the value of which is often underestimated. Like other forms of trace evidence, it does not directly enable the identification of an individual as the source of the recovered material—a limitation that may appear, at first glance, as a weakness. However, fiber analysis should not be viewed in opposition to DNA analysis, but rather as a complementary discipline: while DNA leads to identification, fibers can lead to the reconstruction of criminal activity !

The role of the expert is therefore critical. Beyond reporting analytical observations, the expert’s main responsibility is to inform the reader of the report about the interpretative value of the analytical results. While a DNA expert can, without risk of misunderstanding, report a match between the suspect’s genetic profile and the trace recovered from the victim’s neck, a fiber expert must exercise greater caution when interpreting the correspondence between fiber traces and the suspect’s clothing.

The key criterion for such interpretation lies in what is known as the rarity of the fibers analyzed. Forensic literature identifies the most common fiber types as primarily cotton, followed by polyester, particularly in black, grey, or blue shades. These fiber types are therefore more likely to produce coincidental matches due to their high prevalence in the textile market. Other, less common fiber types can be regarded as rarer, thereby adding greater evidential weight to an analytical correspondence between trace fibers and the suspect’s garments. Beyond published data, the ideal way to assess rarity is through access to a fiber database or by relying on extensive professional experience accumulated over many years in the field. The creation of a European fiber database has been under discussion for over a decade and continues to represent a promising initiative that may finally come to fruition in the coming years.

A transparent way to qualify the results of a fiber examination is to formulate weighted conclusions derived from an evaluative approach, particularly one based on Bayesian reasoning. To this end, the expert works with two competing hypotheses and assesses the likelihood of the analytical results under each. These hypotheses can be framed at different levels, but the central focus of fiber analysis is most often activity level. At this level, the first hypothesis (typically the prosecution hypothesis) reflects what the suspect is alleged to have done, while the second (the defense hypothesis) represents the suspect’s own account of events. This ensures that the expert considers both perspectives—prosecution and defense— when evaluating the findings. In this evaluative process, the expert naturally takes into account not only the rarity of the fibers but also the quantity and distribution of the traces, along with other case-specific factors such as transfer mechanisms, persistence, and background contamination. The evaluation ultimately tips the balance in favor of one hypothesis or the other, with a certain degree of strength. This weighting is explained in an annex to the expert report, enabling the reader to understand the strength of the conclusion (weak, moderate, or strong). Generally speaking, a fiber examination may yield strong conclusions supporting intense contact between the suspect and the victim, as opposed to the legitimate contact the suspect may claim. The fiber trace mapping on the victim’s body can reinforce these conclusions by indicating preferential areas of contact. In the end, a suspect who provides a plausible explanation for their presence or for their DNA being found at the crime scene may still find themselves betrayed by their clothing !

Sources :

- De Wael, Lepot, Lunstroot & Gason, 10 years of 1:1 taping in Belgium— A selection ofmurder cases involving fibre examination, Science & Justice 56 (2016) 18-28.

- Lau, Spindler & Roux, The transfer of fibres between garments in a choreographed assault scenario, Forensic Science International 349 (2023) 111746.

- Sheridan et al., A quantitative assessment of the extent and distribution of textile fibre transfer to persons involved in physical assault, Science & Justice 63 (2023) 509-516.

- Lepot, Lunstroot & De Wael, Interpol review of fibres and textiles 2016-2019, Forensic Science International: Synergy 2 (2020) 481-488.

- Lepot, Vanhouche, Vanden Driessche & Lunstroot, Interpol review of fibres and textiles 2019-2022, Forensic Science International: Synergy 6 (2023) 100307.

- ENFSI, Guideline for evaluative reporting in forensic science, v3.0, https://enfsi.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/m1_guideline.pdf

Tous droits réservés - © 2026 Forenseek