Surreptitious intrusion consists of opening and subsequently closing a locked premises in the absence of a key. The forced entry is effected by means of one or more specific instrument(s), and will not necessarily damage the lock. Only a specialized examination can establish whether such an opening actually occurred and how it was performed. The expert must have an exact knowledge of how the various families of locks operate, be proficient in all possible methods of forced entry — destructive or non-destructive — and understand the physical and mechanical principles involved.

Although this field is relatively little known, surreptitious intrusion — namely the opening and closing of a locked premises without a key — is nonetheless defined by the legislator.

The French Penal Code indeed recalls, in its article 311-5, paragraph 3, concerning aggravated theft, that one of the following circumstances is established: “3° When it is committed in premises … by entering the premises by guile, forced entry or climbing.”

“Breaking and entering” is defined in Article 132-73 of the Penal Code1 as follows: “Breaking and entering consists of the forcing, damaging or destruction of any locking device or any type of enclosure. Also assimilated to forced entry is the use of false keys, unlawfully obtained keys, or any instrument that may be fraudulently employed to operate a locking device without forcing or damaging it.”

Thus, the legislator:

• Acknowledges the possibility that a locked device may be opened without its legitimate key and without damage;

• Considers this modus operandi as an aggravating circumstance;

• Assimilates this modus operandi to “classical” breaking and entering (involving breakage).

Whether in the context of criminal law or in relation to insurance (for which theft “without forcible entry” is often a standard exclusion clause), it is essential to be able to determine the reality of such a burglary.

How can it be determined?

Forcible entry carried out using one or more specific instrument(s) will not necessarily damage the lock. This type of opening—by its nature non-destructive—remains fraudulent and therefore punishable under the law. But how can one know whether such an opening actually took place, and by what means? Only a specialised forensic examination can provide answers to these questions.

Moreover, what is the factual reality of these practices?

A staple of action films, is opening a door without force or damage truly possible? Beyond the simple credit card slipped between the doorjamb and the door (the ‘classic’ unlocking method that anyone who has ever accidentally shut their door with the keys inside has in mind), is this type of opening actually feasible in practice? Is it possible to unlock a door with a five-point locking system—or even an armoured door—without leaving obvious traces?

In this article, we will focus on presenting the ‘invisible’ extent of so-called “subtle” break-ins, and on the expert work that can be carried out to “make locks speak”.

Is a non-destructive, trace-free “subtle” forcible entry possible? And if so, how does it work?

It is commonly accepted that to open a “real” lock (i.e., other than very basic locks) without using the legitimate key, one must either break the key itself or break the element to which the lock is attached, or one of the components that secure the assembly (door, frame and bolt). Yet it is possible to target the lock mechanism itself and thereby operate it “as if the legitimate key were present,” without actually inserting that key.

During a “lock-picking” for example (one of the “soft” techniques among more than a dozen others), the lock can be made to “turn” without the key inside. It then becomes possible to unlock the door. One can even relock it easily without having to pick the lock again. After the opening and subsequent closing of the lock, no trace is visible from the outside and the lock continues to function as before.

Which locks and, more broadly, which security systems are concerned by these “risks”?

The better conceived a system is, the harder it will be to find a way around it. But every system has weaknesses. With the necessary knowledge and sufficient time, it will always be possible to bypass it. From a security standpoint (for readers who may begin to worry about the effective protection of their front door), combining multiple systems and installing them thoughtfully will provide a satisfactory level of security. Nevertheless, each system taken individually remains susceptible to circumvention. Therefore all types of locks are potentially exposed to this risk and may warrant expert analysis when in doubt.

Are these techniques actually used, by whom and in what circumstances?

In the majority of cases — opportunistic burglaries, offences that already produce abundant traces, etc. — the perpetrator(s) will not necessarily possess the skills required to conduct the intrusive part of their crime stealthily. The use of a crowbar allows much faster execution and, provided that the traces left at the scene do not seriously bother them, offenders often make no effort to conceal their tracks.

Nevertheless, covert intrusion methods may be employed in specific cases where the offenders attempt to minimise any sign of their presence (homicides, thefts of sensitive information, disguised thefts, etc.). The appeal of these techniques is real. Numerous online videos present the various lock bypass methods in tutorial form. Likewise, many specialist shops offer the tools necessary to implement these techniques.

It is unfortunate to note that some manufacturers do not restrict sales of such equipment to law enforcement or licensed locksmiths. Moreover, locksmiths themselves seldom use many of these soft techniques because they are costly in terms of training time and equipment and offer little commercial advantage; they often prefer the simple expedient of drilling. While most of these online tutorials are produced by and aimed at enthusiast pickers, they nevertheless put techniques within the reach of all — and therefore also within reach of persons of dubious intent.

Field observations confirm this: an increasing number of offenders specialise in one or another soft-opening technique, according to their preference for a particular offense. During judicial police operations such as searches, investigators may discover items that appear to be intrusion tools. In those circumstances we are regularly asked to determine whether the items are indeed intrusion equipment and whether they can actually function. Precise identification of these tools can thus direct investigators toward a particular modus operandi or toward a specific vehicle make (when the tools are dedicated to opening vehicles), thereby contributing to the establishment of the truth.

What do the used tools look like?

It depends on the targeted lock type. Some tools are general-purpose and cover a broad range of locks. Others are highly specialised: designed for a single type and model of lock, they are devastatingly effective in the hands of someone who knows how to use them.

When conducting an examination of toolmarks to provide real added value to an investigation, it is also important to distinguish between commercial/manufactured tools — which can be obtained more or less easily from specialist suppliers — and homemade tools that some individuals fabricate themselves (which attest to a degree of know-how and can sometimes indicate their maker). One must also mention the existence of ‘decoy’ or ‘dummy’ tools that may have left traces or be found at the scene, yet are incapable of actually opening the lock in question.

Indeed, some persons may wish to create the appearance of an intrusion (which did not in fact occur, or did not occur in the way suggested). They employ all manner of instruments — possibly leaving few traces to support the narrative of a lock being ‘picked’. Once again, the expert’s task is to determine whether the traces are consistent with the use of a tool that could actually have unlocked the device.”

What traces can be visible following an intrusion?

Non-destructive opening techniques leave micro-traces. Those traces are fundamentally different from the impressions normally produced by a legitimate key in its lock, for a variety of reasons. Examples include:

• The shape and thickness of the tools, which differ completely from those of a key and therefore imprint the surfaces they contact in a different manner.

• When a key is inserted, its rotational movement occurs after a straight, tension-free insertion, so this passage does not excessively stress the lock’s various locking elements. This is not the case during lock-picking, where pronounced pressures or ‘micro-forcings’ must be applied to engage the lock’s security components (the elements that secure it).

• Certain areas inside a lock are never in contact with the key and should therefore show no traces other than original machining. During lock-picking, tools may scrape these locations — presumed pristine — leaving significant and diagnostic traces.

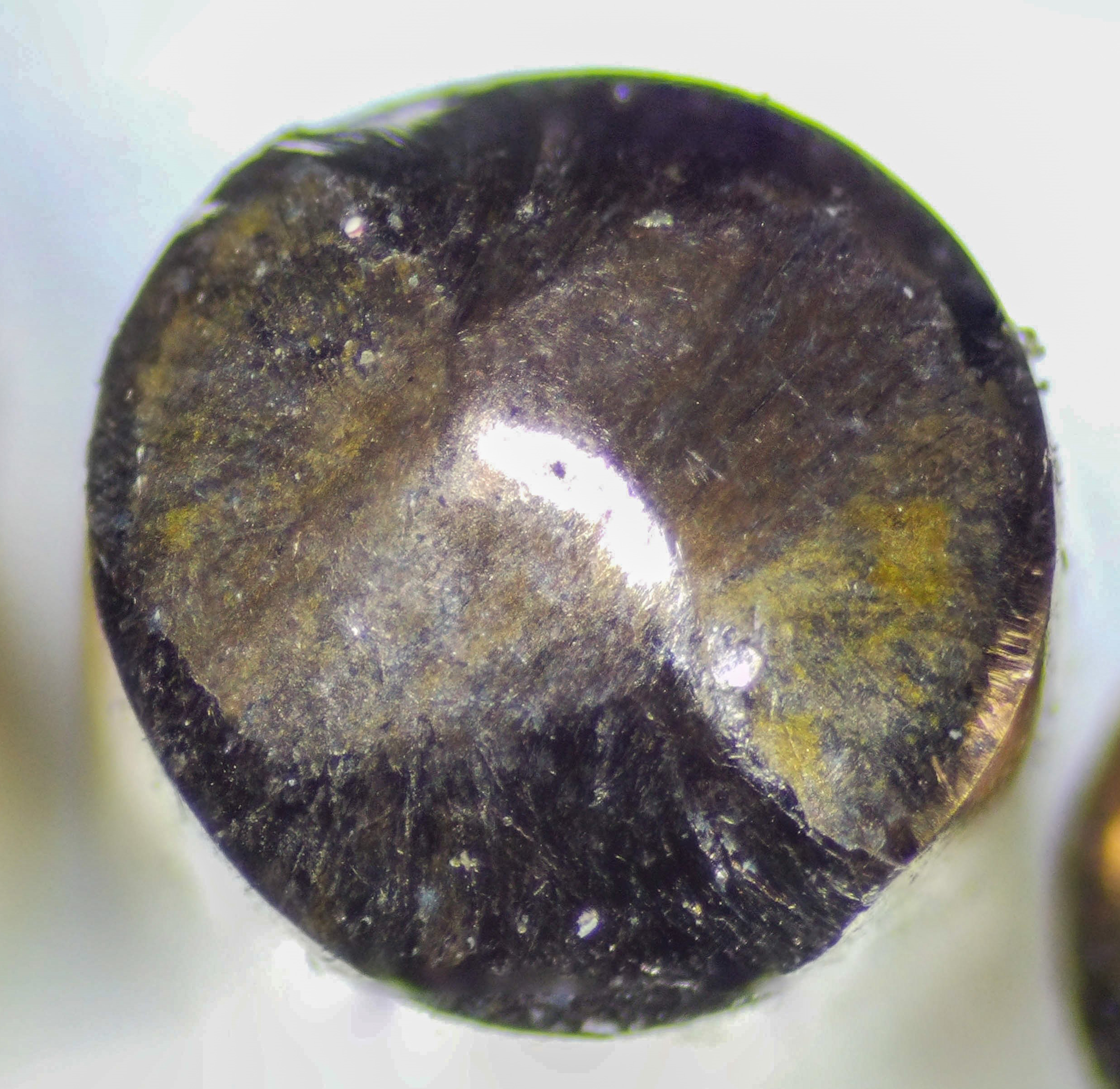

Accordingly, if one knows where and what to look for, it is not only possible to detect that tools have been used, but also to identify with precision the type of attack (including so-called “non-destructive” attacks) the lock has sustained. For example, when using a technique known as ‘bumping’, the tool strikes — sometimes repeatedly — the lock’s pins, producing the characteristic traces illustrated in photo No. 7 below. Traces generated in this way are distinctive of that kind of attack. Demonstrating them can be of great value to the investigation and also helps to profile the “intrusive” methods of the offender.

On what knowledge does the expert rely to identify non-destructive forcible entry?

To examine locks and demonstrate the presence or absence of signs of forced entry, it is essential that the forensic expert have an intimate knowledge of the operating principles of the different families of locks, mastery of the full range of possible forced-entry methods (destructive and non-destructive), and a solid grasp of the physical and mechanical principles at play. The expert must possess in-depth familiarity with existing intrusion tools — including improvised implements — have extensively studied the traces and micro-traces produced by these openings, and know how to disassemble a lock cleanly while absolutely avoiding any contamination that would introduce additional traces. Finally, the expert must be aware of the techniques offenders may use to minimise traces, so as to detect them and determine whether they have been applied.

Searching for traces without knowing what to look for is obviously of little value. In some cases, a lock may display suspicious traces that do not, in fact, result from an intrusion. Such “false positives”2 can be numerous for anyone who lacks real expertise in the discipline.

For these reasons it is imperative, before searching for traces, to identify which technique may have been used and to assess the feasibility of that attack in light of the lock’s environmental context and any associated security elements. Lastly, the expert must be able to put themself in the intruder’s position — that is, be competent to perform these opening methods personally, and even to devise new ones when an innovative modus operandi is suspected. Only an expert capable of thinking like an intruder can truly understand what has been done to a lock. Micro-traces ‘speak’, but the expert must be fluent in the ‘language’ of locks in order to interpret them.

What are the steps of an intrusion expertise ?

A sound forensic examination is difficult to carry out without a proper collection. For this reason it is ideal that the expert collect the lock(s) themselves at the scene. They will take the necessary precautions and fully account for the surrounding environment. When this is not possible, it is preferable that a member of the technical-scientific police (a forensic identification technician or equivalent), who has previously received specific briefing on the subject, perform the collection.

Thus, during collection, the examiner will ensure that nothing is introduced into the lock — or, if removal of the cylinder requires it, that any intervention is carried out following procedures that maximise preservation of potential traces (notably by avoiding contact with the exterior side). They will know which contextual photographs to take so that the expert can situate the lock within its original environment. Likewise, they will ask the proper questions to the lock users. The examination then continues in the laboratory. Preliminary observations are performed and the lock is prepared for analysis. The various components are disassembled, allowing non-destructive observations to be made. The true security level of the lock is assessed and any suspicious traces are sought.

“It is imperative, before searching for traces, to know which technique may have been used and to reconcile the feasibility of an attack with the actual environmental reality of the lock.”

David ELKOUBI

When it is necessary to open the examined item by sectioning and when that is judged the most appropriate course to complete the examination (for example to observe the interior of a cylinder in a location inaccessible without cutting), the sectioning is performed in such a way that it cannot in any way alter the areas of interest to be observed.

Comparisons are made between the examined item and a neutral reference component (often the exterior side of the lock compared with the interior side). Further comparisons are carried out between the traces found and sample toolmarks that may correspond. Finally, a feasibility test is undertaken when material conditions allow. At the end of all these tests, all components are again protected and resealed in order to permit any further observations later if necessary or if those observations need to be disclosed.

How to present a report in an unfamiliar field?

Beyond helping the judge to decide by giving a technical opinion, the expert’s role is to provide magistrates, lawyers and parties with a clear understanding of the technical matter for which the expert was engaged, and to explain the reasoning process that leads him to express such an opinion.

One of the difficulties in this discipline lies in translating sensitive — sometimes even secret — techniques into plain language. These techniques, which an intruder may use, are not readily understood at first glance by a lay reader. For this reason the report details the observations and their implications, explaining how the lock functions under the relevant conditions. A glossary of all technical terms used is appended to the report to render complex terminology simple and comprehensible. Educational clarity is therefore essential so that readers of the report, even without prior knowledge in the field, can grasp the reported observations and their significance.

False positives in intrusion detection

A lock can remain mounted on the same door for decades. Over that period it may undergo many incidents: insertion of a key that was not intended for it, an unsuccessful forcing attempt, deliberate or accidental insertion of foreign objects (for example by children), and so on. In such situations traces may appear on or in the lock. However, those traces do not necessarily indicate an intrusion. The only way to determine whether a trace is truly the consequence of an intrusion is to have a full understanding of the mechanisms of lock-picking and other bypass techniques.

Illustrated beside this text is an example of a pin showing unusual “traces” that are not the result of lock-picking but rather of repeated use of a copied key made from a slightly different blank profile, with a displaced stop. A naïve observation could therefore have led to a false positive (an erroneous conclusion that an intrusion had occurred, when the traces have a different origin).

NOTES :

1 : Concerning the definition of certain circumstances that aggravate, mitigate or exempt penalties.

2 : See the subsection on “false positives for intrusion”.

Article published in EXPERTS No. 149 – April 2020

Tous droits réservés - © 2026 Forenseek