The path that leads from the criminal act to its perpetrator is what we call evidence. In various forms, it is the daily concern of investigators, prosecutors, and judges. Its essentially retrospective nature makes it difficult, unpredictable, and uncertain. One cannot simply turn back time. Years of experience at the Assize Court have taught me that the path separating the most spectacular piece of evidence from a declaration of guilt is a mysterious one: just when you think you have it, it slips away; it may seem obscure, then suddenly becomes compelling. “You who enter here, beware: absolute proof does not exist” could well be the warning engraved above the doors of forensic laboratories. And rightly so.

When it’s too good to be true

He had just killed the elderly lover who had refused to comply with his financial demands when, seized by remorse, he alerted the police in the hope that they might provide the medical care which, he thought, could save him. Without revealing his identity, he fled before the emergency services arrived. Arrested shortly thereafter and confronted with the recording of his call, he admitted to the facts. However, part of the procedure containing his confession was annulled. When the investigation resumed, he chose to change his line of defense and denied the facts, a position he maintained until trial. The presiding judge allowed him ample time during his personality examination so that everyone could become familiar with the sound of his voice. Then came the review of the facts and the playing of his recorded message by the police.

During the adjournment—which is a time for relaxation and informal exchanges—all the judges and jurors recognized the accused’s voice without hesitation. The case seemed settled. Except that…

When the session resumed, and to drive the point home, the prosecution requested that the incriminating message be played again, which was done. At the next adjournment, however, one of the jurors began to have doubts. At the request of the civil party, the message was played again, but after the following recess, three jurors were questioning it. Needless to say, when asked one last time to order the message to be replayed, the presiding judge, now wise with experience, refused. The accused, whose retracted confession was known only to the professionals, might well have been acquitted if the playback of his call continued indefinitely.

The more conclusive a piece of evidence appears, the more cautious one should be

His very distinctive haircut at the time made him recognizable among a thousand: shaved all around the head, leaving only an oval brush of thick black hair on his high, slender forehead. None of these details escaped the video surveillance cameras in the underground car park he had entered barefaced to commit his crime. He was acquitted.

What better proof than to see the victim herself designate her killer with her own blood—moreover, by making a spelling mistake she habitually committed? And yet, the conviction of the accused did not prevent the movement which, invoking a miscarriage of justice, ultimately led to his pardon.

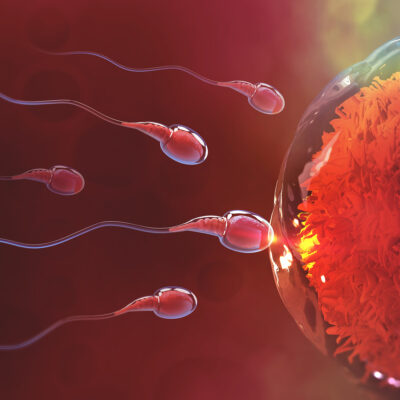

“What are the chances of a mistake in the identification of this DNA profile?” experts are frequently asked. “About one in a billion,” they reply. Until the day it becomes apparent—as I once witnessed—that a material error in an expertise hastily dictated had falsely designated the accused.

Examples of this kind abound, and one may draw a first lesson from them: the more conclusive a piece of evidence appears, the more cautious one should be.

To make progress over and over again

To make progress over and over again

None of this should discourage technicians and experts from constantly striving to refine investigative techniques, and it must be acknowledged that since the discovery of dactyloscopy, the progress made in identifying criminals or exonerating suspects has been remarkable.

Scientific research is continuous, and we can hardly imagine what future advances will further shed light on the truth.

Yet, however far progress may take us, there remains a discontinuity that will always separate the administration of evidence from the declaration of guilt, and which will sometimes frustrate even the finest investigators: that of the work of reason.

Without reproducing in full the address that the presiding judge delivers to the jurors at the end of the trial, before the court withdraws to the deliberation chamber, it is worth quoting a passage contained in what is arguably the most beautiful article of the French Penal Code—Article 353, which establishes the freedom of evidence and the principle of intimate conviction: “The law requires the judges to seek in their conscience what impression the evidence presented against the accused and the arguments for his defense have made upon their reason.” However perfect the evidence may be, its demonstration will always demand an exercise of reason, without which no finding of guilt can be pronounced. And there is nothing more uncertain than reason, even if collegiality greatly reduces its unpredictability.

The challenges of deliberation

It is, for example, particularly difficult to rule on homicidal intent. What does it mean to “intentionally cause death”? Must one probe the exact thoughts of the accused at the precise moment of an act to which he may not even have given a thought an instant earlier, and which he would regret as soon as it was committed? Did he truly intend to cause death? Quite clearly, that is impossible. It must therefore be determined whether death was the logically foreseeable material consequence of an act committed by a conscious and lucid individual.

Similarly, DNA traces found on the complainant’s underwear in a rape case, however categorical they may be, will never dispense with the need to question consent; nor will defense injuries observed on her wrists relieve the court from inquiring into the origins and circumstances of the struggle.

Not to forget—and this may be the essential point—that a trial, where doubt benefits the accused, is the singular exercise that requires judges to determine what they are certain of, in relation to facts to which they were not witnesses.

Back to the basics

Investigators and experts are, of course, fully aware of all this. But to this retrospective approach, which is their daily lot, there succeeds another—this time prospective—which is precisely the mission of that interface known as the Public Prosecutor’s Office. Its role is to assess, with all possible caution given the uncertainty that characterizes the judges’ task, and to guarantee the quality of the evidence that the prosecuting authority will submit to them.

In this uncertain—and, to be truthful, rather vertiginous—procedural chain which, beginning with the initial finding of the crime, must lead with sufficient certainty to the identification of the criminal and the punishment of the offense, it is essential that each actor be fully conscious of his or her own role and of the place he or she occupies.

Tous droits réservés - © 2026 Forenseek