By Benoit Fayet, Defense & Security Consultant at Sopra Steria Next, member of the Strategic Committee of the CRSI, and Bruno Maillot, Data and Artificial Intelligence Expert at Sopra Steria Next, for the Center for Reflection on Internal Security.

Context

La majorité des Français expérimente l’IA sans parfois s’en rendre compte au quotidien : transports, Most French citizens experience AI in their daily lives—through transportation, e-commerce, energy, healthcare, smart homes, agriculture, and more—often without even realizing it. However, AI remains less prevalent in the field of security and in the work carried out by France’s Internal Security Forces (FSI, police and gendarmerie). This is despite the fact that, for years, IT systems and new technologies have already transformed these professions, while the Armed Forces and local authorities have embraced them far more extensively, sometimes for closely related challenges. Today, police officers and gendarmes rely heavily on digital tools, particularly for:

• Their daily activities, using information systems and applications to take complaints, draft reports, consult information on individuals, or through the development and employment of biometric technologies—widely used for identification and authentication, such as fingerprinting.

• Field communications, through dedicated communication networks and mobile devices that assist them during patrols or interventions.

• Monitoring delinquency, especially at the local level or in crisis management situations (video surveillance, command centers, etc.).

• Victim support, with the recent development of online platforms and applications offering the same services as in physical units (filing complaints, reporting incidents, etc.).

Artificial Intelligence represents a decisive lever to reinforce each of these existing digital uses by police officers and gendarmes. The digital tools they already possess, the wealth of data they process daily, and their operational needs could allow this, offering the Ministry of the Interior a new digital revolution.

Indeed, AI is not just another tool; it is a disruptive innovation capable of profoundly transforming the professions and practices of police and gendarmerie personnel, particularly in areas under strain or in crisis, such as criminal investigations. AI could also alleviate many of the daily frustrations that French citizens face regarding security. For example, by reducing the time officers spend on technical or administrative tasks in their units, AI could free them up to spend more time in public spaces, or by enhancing investigative capabilities, it could improve clearance rates for certain offenses. AI’s analytical capabilities in processing complex datasets could also strengthen the fight against organized crime and drug trafficking.Deploying AI systems, however, requires several prerequisites. First and foremost, mastering the national and European legal frameworks governing AI is essential. In addition, clear political guidelines for AI use must be established to ensure acceptance both by police officers and gendarmes themselves and by the public, so that AI is recognized as a tool—not an end in itself. Decision-making and oversight must always remain in human hands, to avoid slipping into the “civilization of machines,” as Georges Bernanos already warned in France Against the Robots (1947).

AI thus represents a decisive lever to reinforce each of the current digital uses by police and gendarmes.

Finally, in a context of growing cyber threats and challenges to our sovereignty, it is essential to ensure the maturity and resilience of the technologies employed, while identifying the most secure tools. A key concern is the lack of technological sovereignty within the EU and France regarding AI solutions, which currently come mostly from outside Europe. It is therefore crucial to identify AI tools that do not expose Europe and France to loss of sovereignty or increased vulnerability to intelligence and influence operations.

The objectives of this article are therefore to analyze the opportunities enabled by the current legal framework for integrating AI into internal security, and to identify concrete, realistic operational uses in the near future that remain technologically controlled and secure.

Early uses of AI underway—will the Paris 2024 Olympics mark a turning point?

Projects already exist in France, whether in public space crime management, administrative activities, or investigative work. Recent innovations in AI have been deployed in connection with the Paris 2024 Olympic Games.

AI used to support decision-making in crime prevention

AI has already been applied because it aligns closely with the core mission of France’s Internal Security Forces (FSI): anticipating and preventing crime. AI has not been developed to predict crime, but rather to better understand and analyze it, and ultimately to assist in decision-making. Crime is not a random phenomenon; it can be analyzed by gathering statistical data on a given territory and feeding it into models that help the FSI operate more effectively in that area (for example, patrol locations and schedules). Analytical methods have been used by the Gendarmerie nationale on non-personal data from the Ministry of the Interior’s Statistical Service for Internal Security (SSMSI), which were then exploited through data visualization to map and monitor the evolution of delinquency within a territory. These are not predictive policing tools—they forecast nothing—but instead provide decision-support analysis based on past events. They offer orientation to FSI units, who cannot realistically cross-check such volumes of data without AI’s analytical capacity. The method, for example, consists of identifying where burglaries or vehicle-related offenses occurred within a defined period and territory in order to infer where the next ones are likely to occur. The aim is to target specific areas and plan police deployments in locations where offenses are at risk of happening, thereby deterring crime.

Other experiments with more predictive tools—extending beyond decision support to actual risk or occurrence prediction—have also been conducted but have not demonstrated significant operational added value.

AI developed to support data processing in criminal investigations

Early AI-based data processing tools have also been developed by the Gendarmerie nationale to assist in investigative phases. Tools can, for example, support FSI in monitoring communications during an investigation by detecting spoken languages in court-authorized telephone interceptions, transcribing and translating conversations, and flagging relevant topics for the case through recurrent neural networks.

Another project has enabled the transcription of videotaped victim interviews and the annotation of procedural documents (persons, places, dates, objects, etc.).

Finally, the Digital Agency for Internal Security Forces (ANFSI), responsible for developing their digital equipment, is experimenting with a tool for producing intervention reports generated by “voice command” on NEO mobile devices.

A decisive shift with the Paris 2024 Olympics?

During the Paris 2024 Olympics, “augmented video” was authorized in Île-de-France under the supervision of the Paris Police Prefecture. For the first time, the law of May 19, 2023 authorized the deployment of AI in video surveillance, within a strict framework explicitly excluding facial recognition. The experimentation focused solely on detecting predefined events, such as abandoned objects, the presence or use of weapons, vehicles failing to respect traffic directions or restricted zones, crowd movements, and fire outbreaks. Article 10 specifically authorized AI processing on certain video streams from fixed cameras to detect these situations, with the goal of securing events particularly exposed to risks of terrorism or threats to public safety. An evaluation committee for these algorithmic cameras is expected to deliver a report by the end of 2024. Several use cases of intelligent video surveillance have already been deemed highly effective, notably those enabling the detection of individuals in restricted zones (facilitating the adjustment of police presence), the detection of crowd density or movements linked to fights, and interventions in urban transport systems.

In summary, while projects exist, they remain limited in scope and far from generalized deployment. Any large-scale adoption must occur within a constrained and evolving legal framework.

A Clear National Legal Framework, Recently Reinforced at the European Level with the AI Act

In France, a strict framework shaped by the CNIL and political efforts to move forward

The CNIL (French Data Protection Authority) has issued several specific recommendations to ensure that AI system deployments respect individuals’ privacy, in line with the provisions of the 1978 « Informatique et Libertés » law and the 2016 European “Police-Justice” directive, which defines data protection rules for information systems used by Internal Security Forces (FSI). Public authorities responsible for AI systems must comply with transparency obligations, making evaluations of such systems public, and follow the principle of “double proportionality.” This principle ensures that AI use is justified both in terms of the operational framework (patrols, criminal investigations, or counter-terrorism threats) and the type of data involved (personal data, statistical data, etc.). For the CNIL, the general rules of data protection (storage duration, independent oversight, etc.) apply equally to AI systems.

At the same time, the Ministry of the Interior and the legislature have advanced along the path outlined by the CNIL—through the 2020 White Paper on Internal Security and the 2023 Loi d’Orientation et de Programmation du ministère de l’Intérieur (LOPMI). These frameworks identified and legally codified specific use cases that may justify AI use in the security sector. They also introduced safeguards for experimentation, particularly in preparation for the Paris 2024 Olympic Games: data anonymization, secure storage, and ensuring that decisions and control remain in the hands of human agents.

The European Commission drafted the AI Act, aimed at regulating the use of AI in Europe, which was adopted by the European Parliament in December 2023 and scheduled to come into effect in August 2026.

A strengthened European framework with the AI Act

Complementing the French framework, the European Commission drafted the AI Act, aimed at regulating the use of AI in Europe, which was adopted by the European Parliament in December 2023 and scheduled to come into effect in August 2026. Its aim is to ensure that AI systems used in the EU are safe, transparent, and under human oversight. Generative AI systems capable of producing texts, code, or images are subject to particular scrutiny. The AI Act then establishes a detailed legal framework for public sector use of AI, including security applications:

• Prohibited AI systems deemed dangerous: biometric identification in public spaces, facial recognition databases (including those based on open-source data), predictive policing systems, etc.

• High-risk AI systems: allowed under strict conditions, requiring documentation, human oversight, compliance procedures, and continuous evaluation (e.g., biometric categorization systems, migration management tools).

• Limited-risk AI systems: permitted but subject to transparency requirements (e.g., object detection systems). (By February 2025, prohibited AI systems must be withdrawn or brought into compliance. By August 2025, high-risk and limited-risk systems must be fully compliant).

It should be noted that the AI Act provides exceptions, particularly for law enforcement operations. Remote facial recognition (via camera or drone) may be permitted, but only under prior judicial authorization and within a strictly defined list of crimes—such as the search for a convicted or suspected serious offender.

Prospects for the Use and Application of AI in Internal Security

Building on the reflections already undertaken and the regulatory framework now in place, it is time to look ahead at the concrete contributions AI could bring to the professions of the national police and gendarmerie. This involves leveraging existing technologies, recent developments—particularly in generative AI—and identifying the conditions required for such use: communication and information-sharing, data access, simplification of technical tasks, data analysis in investigative phases, and more.

AI must support the Internal Security Forces (FSI), without becoming “the agent.” Tasks that may be entrusted to AI must always remain under human primacy in terms of oversight and validation.

It is important to emphasize that the use cases identified in this note are part of a forward-looking perspective. They take into account the regulatory framework described earlier and are grounded in the idea that AI should provide operational added value to the FSI, while safeguarding ethical principles regarding data protection. This approach must remain far removed from the practices of certain non-European countries, which would undermine the French democratic model. AI must support the Internal Security Forces (FSI), without becoming “the agent.” Tasks that may be entrusted to AI must always remain under human primacy in terms of oversight and validation. Delegation to AI should therefore accelerate action and decision-making, without creating dependence. The key lies in identifying appropriate use cases, particularly those involving tasks with little or no added value, so that FSI personnel retain their decision-making capacity and agency.

AI to Optimize Communication and Information-Sharing Among FSI

In today’s deteriorated security environment, communication and data-sharing are critical—whether during routine patrols, interventions requiring situational awareness, or more serious operations such as counter-narcotics or counter-terrorism missions.

Concrete use cases include the ability to centralize and process data from FSI mobile equipment or from video surveillance systems (video, audio, radio, conversations, and calls between units). These capabilities are currently unattainable but could become feasible with AI-powered tools, especially given the ever-increasing volumes of data being collected. Such tools would enhance operational performance by improving situational awareness and could be integrated into the ongoing transformation of FSI communication systems through the deployment of a national high-speed mobile network. AI could thus be a decisive enabler for faster information and intelligence-sharing, ensuring that actionable insights reach police and gendarmes in the field quickly enough to address emerging threats—for example, by detecting weak signals linked to operational drug intelligence units (CROSS) or through partnerships involving local authorities, municipal police, and associations. AI could process and qualify shared information almost in real time.

AI to Generate Knowledge and Support FSI Action in Real Time

As Internal Security Forces (FSI) increasingly produce data through their mobile devices, they operate in an environment where third-party data is also multiplying. To address this dual evolution, a data-valorization strategy leveraging AI could be developed, combining retrospective data analysis (already available in existing decision-support tools) with the enrichment of operational information in real time (e.g., patrol geolocation, AI-generated analytical notes), algorithmic developments, and the integration of external datasets (in compliance with the AI Act). This could include, for instance, analyzing real mobility flows across urban transport networks during an arrest mission or monitoring road traffic to detect accidents and disruptions in real time, thereby enabling faster and better-informed responses.

One of AI’s distinctive features is its ability to automatically flag incidents. When predefined conditions or scenarios are met—such as fights or crowd movements—an AI-based system can automatically generate detailed incident reports and dispatch alerts to FSI units for immediate assessment. This not only accelerates the documentation process but also ensures that minor infractions or disturbances (e.g., acts of vandalism or incivilities) that might otherwise go unnoticed are reported and addressed.

Moreover, the growing volume of available data can provide real-time access to a wider range of information. Tactical awareness could thus be enhanced by combining operational data (patrol geolocation, including other “security producers” such as municipal police or private security, and the geolocation of individuals targeted in an investigation), contextual data (points of interest, population density, infrastructure status), and sensor data (body-worn cameras, etc.). AI could retrieve, structure, and deliver these diverse datasets in real time to FSI officers on the ground, enabling faster intervention times (e.g., automated data transmission).

The challenge in this case lies in clearly defining needs and use cases to ensure relevant, actionable data, and in developing appropriate methods of restitution—such as cartographic visualization or automated integration into the information systems and mobile devices used by FSI.

Applied to these technical tasks, AI-driven automation could help FSI save time in their daily activities, allowing them to refocus on their core mission: being visibly present in the field, patrolling the streets, reinforcing public trust, deterring crime, and preventing delinquency.

AI to Streamline, Accelerate, and Simplify the Administrative and Technical Tasks of FSI

Internal Security Forces (FSI) often lament that a growing share of their working time is consumed by repetitive, burdensome administrative and drafting tasks with little added value. The use of AI for such “back-office” technical tasks is already widespread in other industries, particularly with generative AI, which shifts from passive analysis to active content creation.

Applied to these technical tasks, AI-driven automation could help FSI save time in their daily activities, allowing them to refocus on their core mission: being visibly present in the field, patrolling the streets, reinforcing public trust, deterring crime, and preventing delinquency. One of the key lessons learned from the Paris 2024 Olympic Games is that the visible, large-scale presence of FSI in public spaces was not only effective but also welcomed by the population.

Support procedure drafting, collect information

AI opens the door to numerous functionalities to facilitate—or even eliminate—time-consuming repetitive tasks that dominate FSI daily operations, including drafting official reports (procès-verbaux), arrest records, complaint filings, or investigation notes. In the drafting and transcription phases, AI could accelerate report writing, whether at the station or in the field, by generating automated text or providing suggested formulations (e.g., regulatory phrasing), extracting relevant information from documents, accelerating video review by filtering or selecting scenes via semantic queries, or masking specific segments of documents or video (e.g., identifying relevant portions within large volumes of video using transformers).

The use of AI in this context would rely on recurrent neural networks that process data streams while retaining “memory” of texts, word sequences, or sentence patterns, much like biological neural networks—but with exponentially greater computational power. This can add real value to drafting and transcription tasks.

To further enhance efficiency, AI could also amplify the capabilities of tools already deployed by the Ministry of the Interior—for instance, integrating natural language processing into everyday applications (e.g., generating reports or official records via voice commands directly in the field). In this sense, AI is a powerful enabler, giving FSI more time to focus on high-value tasks—for example, during periods of police custody, allowing officers to interrogate suspects or work on case files instead of devoting limited time to repetitive administrative and technical tasks. (By law, police custody lasts 24 hours but may be extended to 48 hours if the alleged offense carries a prison sentence of more than one year, and up to 96 hours for specific crimes such as drug trafficking, terrorism, or organized crime.)

Fact-Checking and Assisting in Evidence Gathering

The collection of statements, testimonies, and various interviews forms the backbone of investigative work and often represents the first step in uncovering contradictions or verifying facts. The hundreds of documents that typically enrich a case file are still largely transcribed manually by investigators. Increasingly, however—and whenever required by law—these statements are filmed and recorded. In the future, they could be directly recorded and automatically transcribed by an AI-based system, thereby generating data that can be quickly processed and cross-checked by FSI. This would allow investigators to focus on analysis and fact-finding, ultimately improving case resolution rates.

This aggregation capability is one of the major contributions of AI, which must be considered within the legal framework set by the CNIL. Properly deployed, it could give FSI easier and faster access to the information they need.

Searching for Information Across Information Systems

L’IA pourrait aussi permettre de faciliter les travaux de recherche d’informations sur un individu ou un groupe d’individus interpellés ou recherchés. Ces phases de recherche sur des données biographiques, des données sur des antécédents judiciaires sont le quotidien des FSI et se font dans les différents fichiers de police mis à leur disposition (FPR – Fichier des Personnes Recherchées, TAJ – Traitement des antécédents judiciaires, etc.). Ces fichiers de police fonctionnent en silo et communiquent peu entre eux, notamment dans le but de respecter leurs finalités de traitement, conformément aux principes de la CNIL. Ainsi, le partage d’informations entre les fichiers est limité à des interfaçages applicatifs, et les FSIAI could also simplify information retrieval tasks on an individual—or a group of individuals—who have been arrested or are being sought. These searches, which involve biographical data and criminal records, are a daily routine for FSI and are performed using multiple police databases (such as the FPR – Fichier des Personnes Recherchées or the TAJ – Traitement des Antécédents Judiciaires). These systems function in silos and communicate very little with each other, partly to comply with their specific legal purposes as required by CNIL principles. As a result, information sharing between databases is limited to certain interfaces, and investigators often need to consult several systems simultaneously. Given the proliferation of data and the sheer volume to be analyzed daily, AI could overcome this challenge by aggregating information and delivering it directly to FSI. This aggregation capability is one of the major contributions of AI, which must be considered within the legal framework set by the CNIL. Properly deployed, it could give FSI easier and faster access to the information they need. —whether for personal safety during an arrest (e.g., understanding how to approach a specific individual), improving the effectiveness of public safety checks (e.g., ensuring the correct identification of a person during a stop), or supporting police investigations. For example, AI could support cross-referencing between different data sources, which is now authorized between Automatic License Plate Recognition (ALPR/LAPI) systems and other databases, such as stolen vehicle registries, vehicle insurance records, or the automated traffic enforcement system. Moreover, AI’s aggregation capabilities could streamline the process of freezing bank accounts through the Ministry of Economy and Finance’s information systems, thereby improving the recovery of fines—including amendes forfaitaires délictuelles (AFD, flat-rate criminal fines)—or directly targeting the financial assets of certain offenders, a political priority emphasized by the Minister of the Interior, Bruno Retailleau. à l’assurance des véhicules ou encore le système de contrôle automatisé.

Securing Police Databases and Their Use

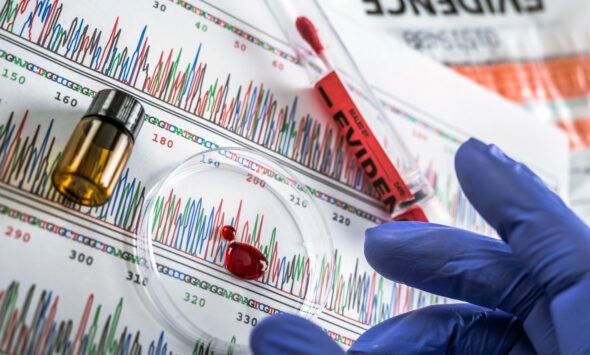

In addition to consultation, a recurring task also involves “feeding” police databases with information about individuals who have been arrested or are wanted—data that includes descriptions of facts, offenses, and most importantly, identity details (biographic or biometric). This stage is critical, particularly in the acquisition of biometric data, as it determines the quality of the databases and ensures that, in the case of an offense or crime, suspects or victims can later be accurately identified. The computing power of AI algorithms can identify and highlight minutiae (specific points on a fingerprint) with greater precision than the human eye, leading to more accurate comparisons.

The interrogation of police databases containing fingerprint or genetic data could also be automated with AI, enabling faster and more reliable comparisons. Moreover, the deployment of automated quality-control checks could secure data acquisition, for example through an application assisting in fingerprint capture and automatically detecting non-compliant fingerprint images. Similarly, AI could enhance the processing of latent fingerprints left unintentionally on surfaces, which are often partial, blurred, or of poor quality. By extrapolating from recognized patterns, AI could fill in missing segments, enabling stronger matches.

During investigative phases, AI could also be leveraged to search data and cross-comparison with large databases.

AI to Strengthen Analytical Activities of FSI and Better Combat Delinquency

Handling Large Volumes of Data

AI offers opportunities to compute and automate certain tasks for FSI faced with vast amounts of data, whether in administrative screening activities or in criminal investigations. For example, Interior Ministry agents are tasked with vetting individuals applying for sensitive jobs, requiring them to check across all relevant police databases. In these mass data-analysis activities, AI could add value by accelerating and securing checks, allowing human analysts to focus on critical points, and ultimately enabling faster decision-making. AI could also optimize oversight activities by automatically detecting abnormal database consultations.

During investigative phases, AI could also be leveraged to search data and cross-comparison with large databases to improve clearance rates—for example, through DNA comparison against the national DNA database (FNAEG). DNA analysis is one of the most widely used forensic methods for identifying perpetrators of crimes. Moreover, AI could support judicial investigations, where case files are becoming increasingly voluminous and complex. Faced with the multiplicity and heterogeneity of data, AI’s processing power allows for faster classification, linkage, and recall of all relevant information within very short timeframes. Investigators could therefore analyze and cross-check evidence more efficiently, with fewer errors, ultimately improving case resolution.

Additionally, most data from criminal investigations are stored on hard drives for archiving. Tools capable of cross-referencing and linking these datasets are needed to identify evidence within massive amounts of stored information. AI could perform this classification and connection work, linking facts and evidence contained in judicial files. A key challenge lies in managing large volumes of judicial data to accelerate investigative processes—whether on the street or during interventions—enabling quicker decision-making. Here again, the definition of clear use cases and the pre-training of AI systems are essential to ensure the relevance of analyses, for instance through the generation of synthetic data.

Better Analyzing and Interpreting Images, Sounds, and Large-Scale Data

Generative AI introduces new techniques for analyzing and interpreting images. These developments can greatly enhance investigative work by processing large volumes of heterogeneous images, extracting requested elements from them, and understanding complex queries. Such solutions could support investigative phases through the analysis of crime scene photos, traffic accident images, or footage from urban supervision centers (CSU), helping to identify items of interest (vehicles, persons, etc.). Likewise, computer vision could become a major asset through the use of neural networks capable of interpreting and analyzing complex visual information on a large scale. Inspired by the human brain, these networks could, for example, be applied to aerial or satellite imagery to detect specific surfaces—useful for national police and gendarmerie to identify targeted vehicles, drug-dealing spots, and more.

AI would also improve vigilance in monitoring video surveillance feeds, thereby increasing efficiency and accelerating responses to suspicious situations (drug-dealing locations, brawls, gatherings, etc.). Indeed, it is estimated that after just one hour of real-time video monitoring, an operator loses concentration and may miss up to 50% of events. In the future, operators could rely on AI systems to flag events automatically, allowing them to focus on verification, analysis, and decision-making rather than continuous live monitoring.

AI can accelerate the detection process currently carried out by human eye, using image-analysis and behavioral-analysis tools based on convolutional neural networks to identify objects, actions, or individuals. Current machine learning techniques already allow the retrieval of a specific person’s photo, object, or weapon from thousands of stored photos on a computer or smartphone. AI’s object- and shape-recognition capabilities therefore represent a significant operational advantage.

Finally, AI can make major contributions through voice recognition technologies, capable of deciphering unique vocal characteristics, converting speech into models that can be processed and compared to stored voiceprints (samples from telephone calls or recordings).

AI would thus enable greater vigilance in video surveillance monitoring, improving efficiency and accelerating responses to suspicious situations.

Mieux analyser et détecter rapidement

Open-source intelligence gathering (OSINT, SOCMINT) has become a common practice due to the abundance of available data (social networks, etc.). AI support is fundamental in these phases, enabling rapid detection and characterization of urgent or dangerous situations at a faster speed than criminal networks or drug traffickers can erase their digital traces. For example, AI can be used for monitoring information flows “information noise” through web scraping, while respecting the AI Act framework (which excludes facial recognition), to detect and counter propaganda or disinformation. Using advanced AI and machine learning algorithms, vast amounts of data can be analyzed at high speed to identify patterns, keywords, or visual content—decisive in large-scale investigations such as narcotics trafficking or organized crime. Moreover, AI-driven systems can be trained on known propaganda or disinformation material, proactively spotting and flagging new content with similar features, ensuring swift and effective removal before it spreads.

To ensure the efficiency of these tools, the challenge lies in the ability to process both structured data (words, signs, numbers, etc.) and unstructured data (images, sounds, videos, etc.) at a large scale, relying on platforms and self-learning AI models capable of reformatting and making them exploitable. Automated language-analysis technologies powered by AI can extract and analyze written content across data volumes impossible to process manually.

AI also offers faster response times via machine learning, by training systems with massive datasets so they progressively learn to handle them autonomously. For instance, tracking the escape vehicle of a criminal suspect through surveillance cameras could be processed far more quickly by AI than by human analysis, leaving human investigators free to focus on data interpretation and oversight.

AI could support operators at an urban supervision center by detecting waste, abandoned objects, weapons, or fire outbreaks; calculating vehicle dwell time; monitoring parking near sensitive sites; identifying red-light violations or line crossings; and analyzing crowd movements.

AI to Enhance Investigative Capabilities and Case Solving

The sheer volume of data to be processed in investigations (video streams, images) has reached a level where exploitation is no longer possible without digital assistance. The massive increase in digital data places a heavy burden on the ability of Internal Security Forces (FSI) to handle it. The use of AI has therefore become not just an asset but a necessity—and, in the long term, an indispensable condition for effectively exploiting data or information that may contribute to establishing evidence. FSI must be equipped with tools to streamline video analysis, helping investigators avoid the need to review entire video or image sources manually. This would save time, increase efficiency, prevent concentration loss during long viewing sessions, and allow investigators to focus on higher-value analytical tasks. Without AI, it is likely that investigators would, in some cases, forego systematically analyzing all available video sources, thus missing out on particularly valuable digital evidence.

In addition to videos, investigators often rely on witness statements, bank records, phone logs, and testimonies—sources that could be processed by AI-powered software to flag inconsistencies, map data across time and space, or generate relational diagrams. Entering such data manually from paper or digital records is slow and labor-intensive. AI tools could detect key elements directly within texts, identify and classify them by meaning, and automatically generate relational diagrams. This would offer real added value by enabling real-time mapping of relationships and links from recordings or digital data, as well as suggesting follow-up questions to help investigators identify and apprehend suspects faster.

AI could also enable real-time detection across massive data flows of forged documents and fraud—tasks beyond human capacity—thereby improving case resolution rates. In identity management, applications are numerous, as in road safety, whether for combating driver’s license fraud, insurance fraud, or repeated fraudulent practices (disputes over traffic fines, registration fraud, vehicle theft, etc.). Furthermore, with AI-driven analysis, investigators could process millions of financial transactions, detecting suspicious fund movements indicative of money laundering schemes otherwise difficult to uncover. This would concretely improve the ability to analyze and understand criminal networks, connections, and environments, detect hidden links, and strengthen the fight against organized crime (drug trafficking, etc.). Recent dismantling of encrypted communication systems such as EncroChat or Matrix has highlighted the crucial role of advanced data analysis.

Finally, AI could help secure the use of images, documents, and videos by FSI by automating the redaction of passages or sections of documents to strengthen personal data protection and privacy compliance in line with CNIL and AI Act recommendations. For example, convolutional networks could detect and filter pre-defined elements in images. AI could also be used with precision and speed to exploit tools such as body-worn cameras to establish evidence—for instance, in cases where FSI conduct during interventions is challenged.

AI could also streamline procedures such as filing complaints or renewing administrative documents.

AI to Strengthen Victim Support

In recent years, the Ministry of the Interior has deployed online platforms and applications enabling citizens to report and declare incidents, file complaints (Perceval—reporting credit card fraud; Pharos—reporting illegal online content; THESEE—reporting cyber scams; PNAV—reporting crimes against persons and victim support), or access online information (locating a police station, etc.). These sites provide citizens with practical tools and represent a concrete way to expand data-driven practices. They also generate a new “data source,” often structured (words, numbers, signs, etc.), which could be further developed and exploited by AI for mapping reports, locating crime data, or analyzing crime types by area. Such processed data could then be made available to FSI in the field, allowing for quicker interventions (e.g., automated statistics, automatic reporting).

These platforms also open opportunities to rethink new modes of intelligence and information collection. They could help strengthen the detection of even weak signals using AI in a security context where diversifying channels for incident reporting is critical.

AI to Transform Police-Public Relations

AI could also streamline procedures such as filing complaints or renewing administrative documents by introducing conversational assistants (chatbots or callbots) to provide information or services.

By integrating AI capabilities into complaint-management software, police and gendarmes handling victims in their units could respond faster and more effectively (e.g., automatic scheduling of appointments via categorization). Online complaint services could also be enhanced, automatically registering complaints, analyzing them, and directing victims toward the most appropriate solution (automated confirmation, video-complaint with an officer, in-person appointment, etc.).

Recommendations and conclusion: Developing AI within a Clear and Secure Framework

The successful experiences from the Paris 2024 Olympic Games and recent technological advances highlight the urgent need to reflect on AI’s role in security. Given the deteriorating security context in France, increasingly organized crime, and the high demands of complex law enforcement professions where digital tools are already pervasive (investigation, forensics), AI is becoming an essential resource to help resolve cases, clarify facts, and provide robust solutions for FSI.

AI is not an end in itself but a powerful lever—just as IT systems and biometrics once were—and should be understood as such. To achieve this, it is vital to ensure:

• A clear political framework to reassure society and stabilize legislation.

• A ministerial strategy to secure FSI’s use of AI, supported by clear governance.

• Identifying the right use cases for AI, the right projects, and creating the conditions to scale up: ensuring data quality to guarantee tool efficiency, robustness, resilience and security-by-design of systems to limit vulnerabilities to cyber risks posed by criminals skilled in such threats, system auditability to understand and improve the results produced by these systems, etc.

• An integrated approach — ethical, legal, and technological — to systematically address the importance of the data being handled, requiring the establishment of balanced measures in terms of cybersecurity and transparency toward society.

• An identification of AI tools whose use does not come at the cost of France’s sovereignty or increase vulnerability to data leaks, cyberattacks, or intelligence and influence operations (information warfare, etc.)

Taking these technological steps is necessary if France is to meet the pressing challenges of public order and security it faces today.

Tous droits réservés - © 2026 Forenseek